No, this isn’t some kind of multiple-book book review. This is an ungodly silly claim that I can actually read three books at once. Silly, but true.

Now, I don’t claim to be a three-armed mutant with six eyes or anything. And I am relatively sure I only have one brain. But, remember, I was a school teacher who could successfully maintain a lesson thread through discussions that were supposed to be about a story by Mark Twain, but ventured off to the left into whether or not donuts were really invented by a guy who piloted a ship and stuck his pastries on the handles of the ships’ wheel, thus making the first donut holes, and then got briefly lost in the woods of a discussion about whether or not there were pirates on the Mississippi River, and who Jean Lafitte really was, and why he was not the barefoot pirate who stole Cap’n Crunch’s cereal, but finally got to the point of what the story was really trying to say. (How’s that for mastery of the compound sentence?) (Oh, so you could do better? Really? You were in my class once, weren’t you.) I am quite capable of tracking more than one plot at the same time. And I am not slavishly devoted to finishing one book before I pick up the next.

I like reading things the way I eat a Sunday dinner… a little meatloaf is followed by a forkful of mashed potatoes, then back to meat, and some green peas after that… until the whole plate is clean.

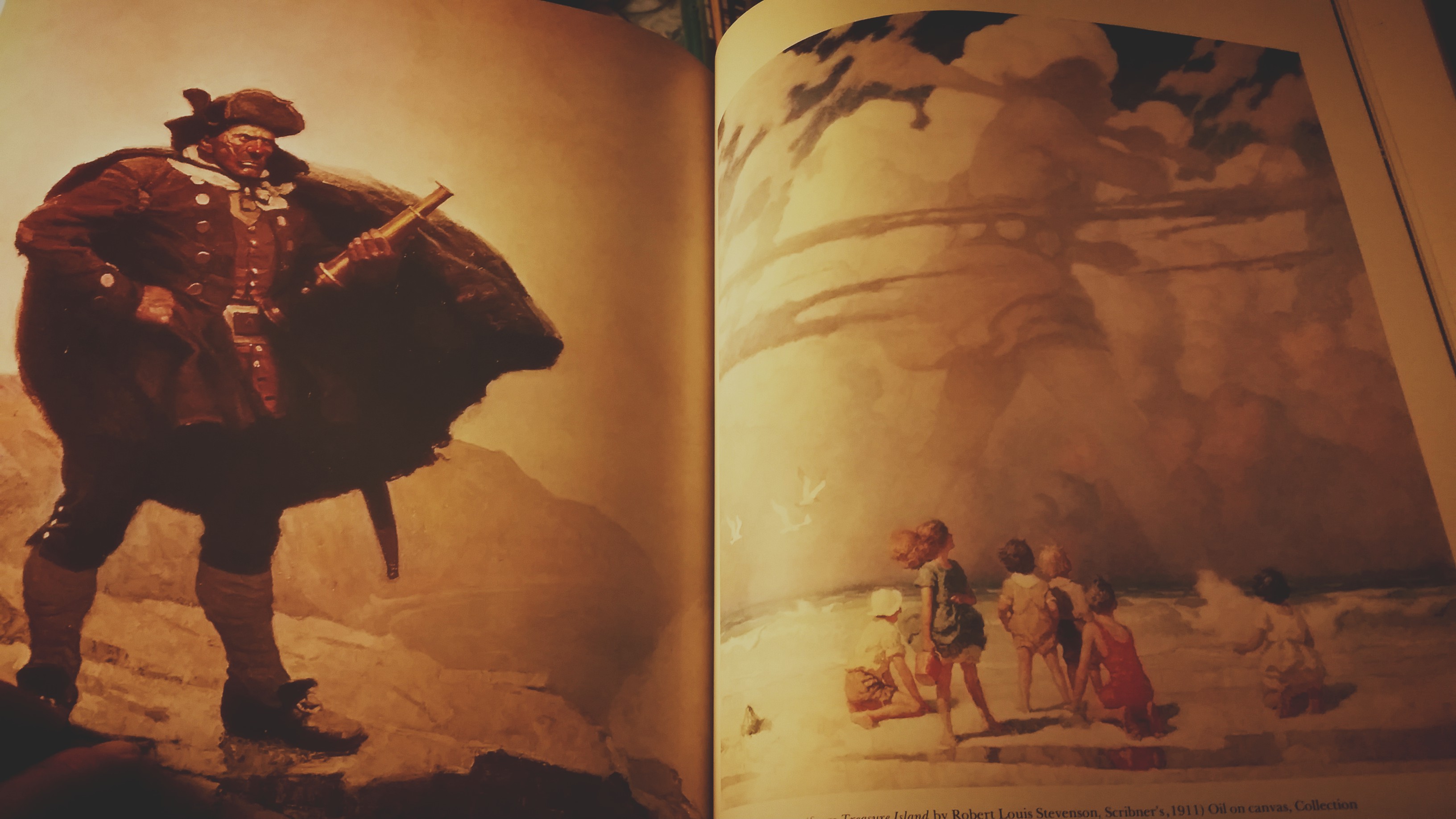

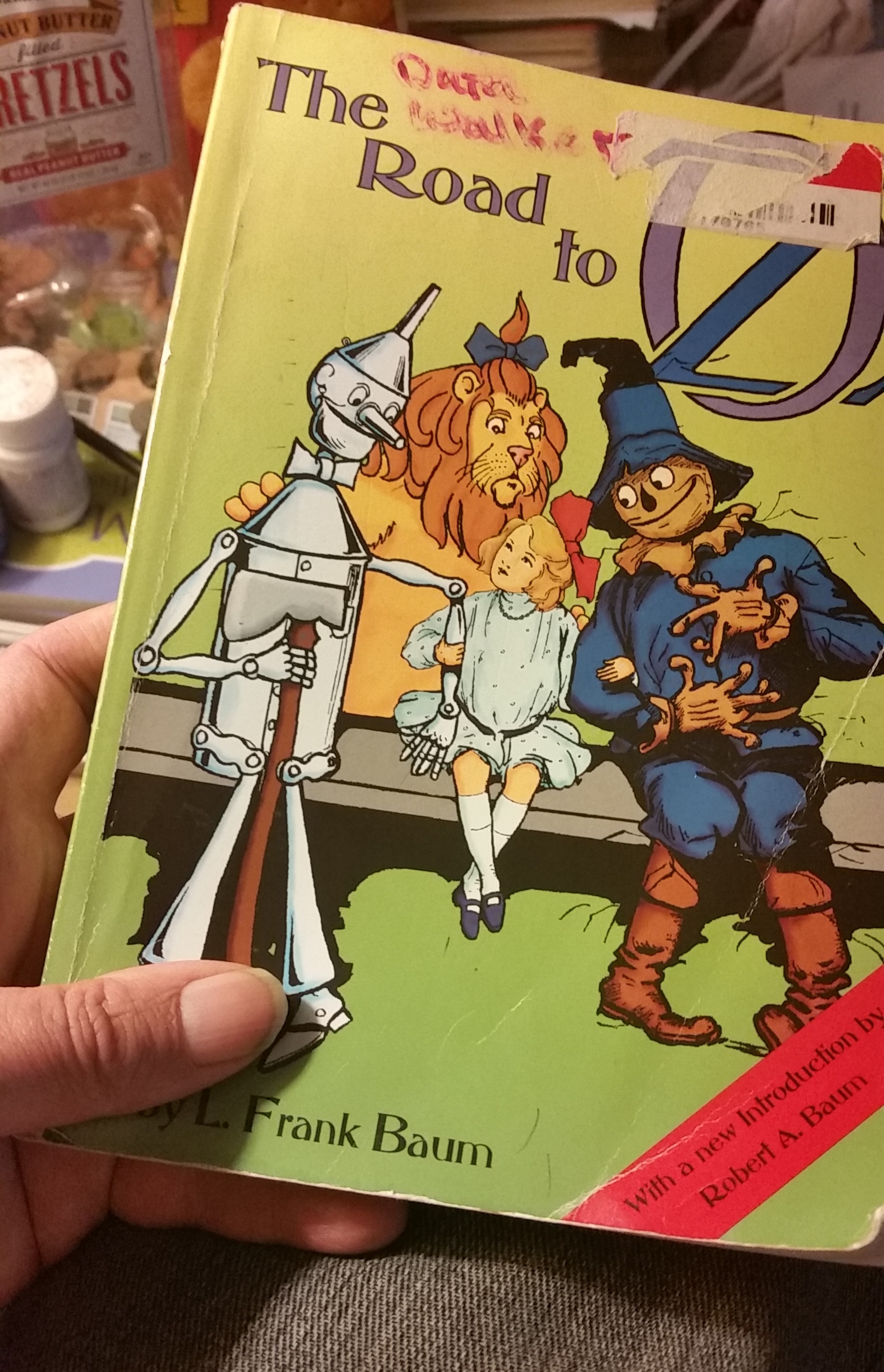

Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson is the meatloaf. I have read it before, just as I have probably had more meatloaf in my Iowegian/Texican lifetime than any other meat dish. It’s pretty much a middle-America thing. And Treasure Island is the second book I ever read. So you can understand how easy a re-read would be. I am reading it mostly while I am sitting in the high school parking lot waiting to pick up the Princess after school is out.

Lynn Johnston’s For Better or Worse is also an old friend. I used to read it in the newspaper practically every day. I watched those kids grow up and have adventures almost as if they were members of my own family. So the mashed potatoes part of the meal is easy to digest too.

Lynn Johnston’s For Better or Worse is also an old friend. I used to read it in the newspaper practically every day. I watched those kids grow up and have adventures almost as if they were members of my own family. So the mashed potatoes part of the meal is easy to digest too.

So that brings me to the green peas. Green peas are good for you. They are filled with niacin and folic acid and other green stuff that makes you healthier, even though when the green peas get mashed a bit and mix together with the potatoes, they look like boogers, and when you are a kid, you really can’t be sure. Terry Pratchett and Stephen Baxter wrote this book The Long War together. And while I love everything Terry Pratchett does, including the book he wrote with Neil Gaiman, I am having a hard time getting into this one. Parts of it seem disjointed and hard to follow, at least at the beginning. It takes work to choke down some of it. Peas and potatoes and boogers, you know.

But this isn’t the first time I have ever read multiple books at the same time. In fact, I don’t remember the last time I finished a book and the next one wasn’t at least halfway finished too. So it can be done. Even by sane people.

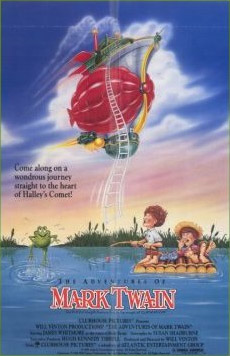

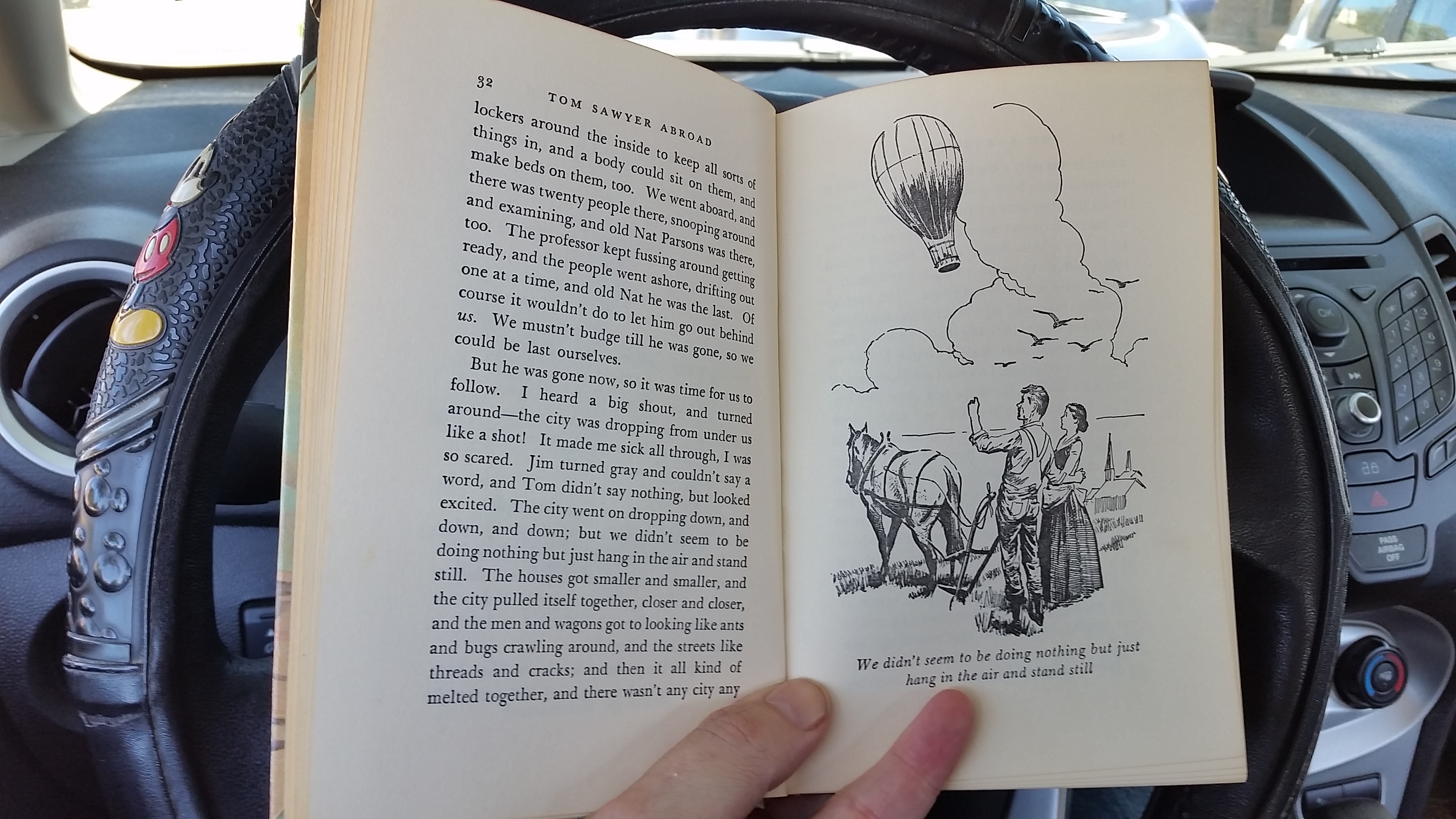

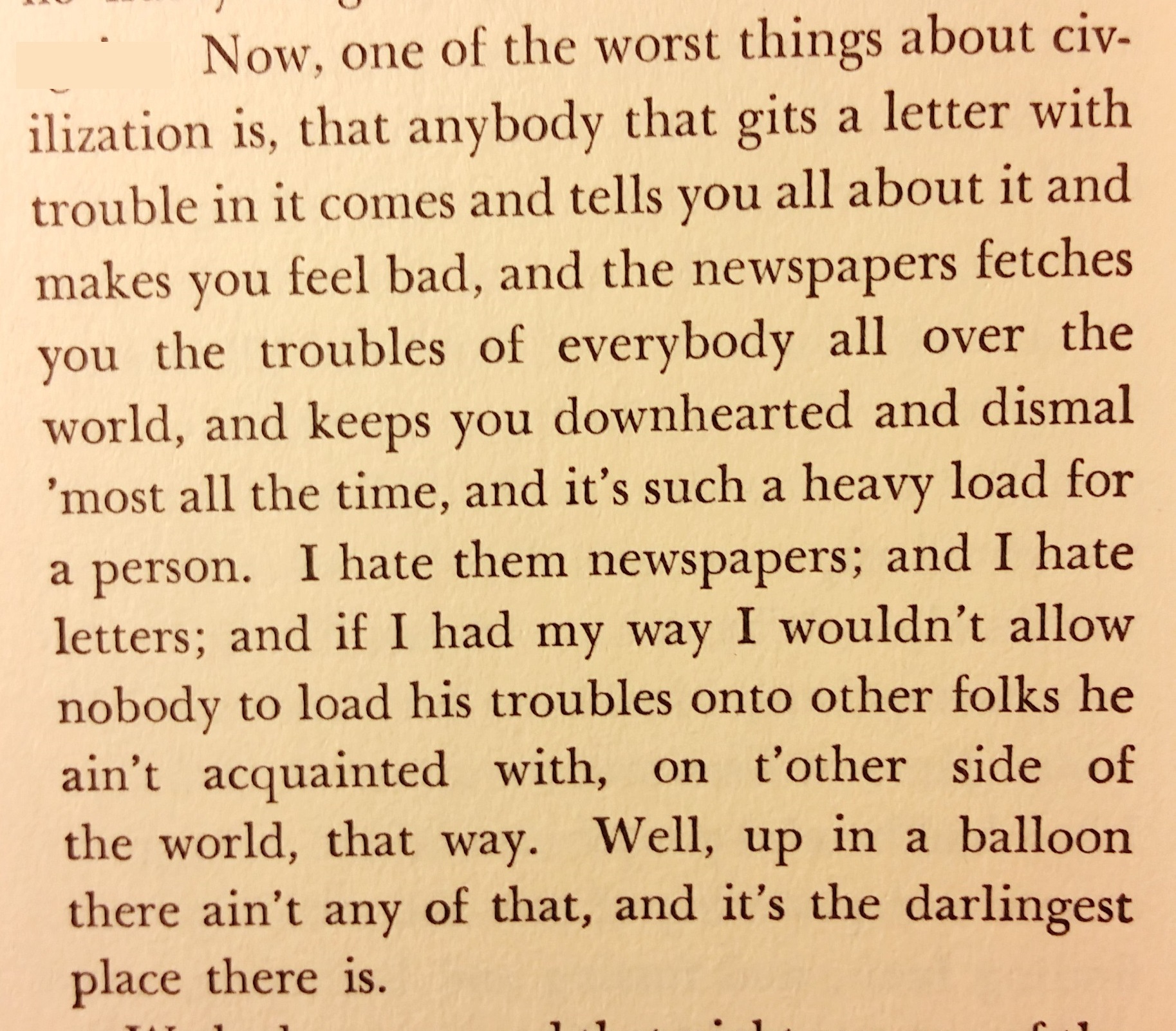

During my middle-school teaching years I also bought and read copies of The Prince and the Pauper, Roughing It, and Life on the Mississippi. I would later use a selection from Roughing It as part of a thematic unit on Mark Twain where I used Will Vinton’s glorious claymation movie, The Adventures of Mark Twain as a way to painlessly introduce my kids to the notion that Mark Twain was funny and complex and wise.

During my middle-school teaching years I also bought and read copies of The Prince and the Pauper, Roughing It, and Life on the Mississippi. I would later use a selection from Roughing It as part of a thematic unit on Mark Twain where I used Will Vinton’s glorious claymation movie, The Adventures of Mark Twain as a way to painlessly introduce my kids to the notion that Mark Twain was funny and complex and wise.

My Bookish Journey (Finale)

Like every real, honest-to-God writer, I am on a journey. Like all the good ones and the great ones, I am compelled to find it…

“What is it?” you ask.

“I don’t know,” I answer. “But I’ll know it when I see it.”

“The answer?” you ask. “The secret to everything? Life, the universe, and everything? The equation that unifies all the theories that physicists instinctively know are all one thing? The treasure that pays for everything?”

Yes. That. The subject of the next book. The next idea. Life after death. The most important answer.

And I honestly believe that once found, then you die. Life is over. You have your meaning and purpose. You are fulfilled. Basically, I am writing and thinking and philosophizing to find the justification I need to accept the end of everything.

And you know what? The scariest thing about this post is that I never intended to write these particular words when I started typing. I was going to complain about the book-review process. It makes me think that, perhaps, I will type one more sentence and then drop dead. But maybe not. I don’t think I’ve found it yet.

The thing I am looking for, however, is not an evil thing. It is merely the end of the story. The need no longer to tell another tale.

When a book closes, it doesn’t cease to exist. My life is like that. It will end. Heck, the entire universe may come to an end, though not in our time. And it will still exist beyond that time. The story will just be over. And other stories that were being told will continue. And new ones by new authors will begin. That is how infinity happens.

I think, though, that the ultimate end of the Bookish Journey lies with the one that receives the tale, the listener, the reader, or the mind that is also pursuing the goal and thinks that what I have to say about it might prove useful to his or her own quest.

I was going to complain about the book reviewer I hired for Catch a Falling Star who wrote a book review for a book by that name that was written by a lady author who was not even remotely me. And I didn’t get my money back on that one. Instead I got a hastily re-done review composed from details on the book jacket so the reviewer didn’t have to actually read my book to make up for his mistake. I was also going to complain about Pubby who only give reviewers four days to read a book, no matter how long or short it is, and how some reviewers don’t actually read the book. They only look at the other reviews on Amazon and compose something from there. Or the review I just got today, where the reviewer didn’t bother to read or buy the book as he was contracted to do, and then gave me a tepid review on a book with no other reviews to go by, and the Amazon sales report proves no one bought a book. So, it is definitely a middling review on a book that the reviewer didn’t read. Those are things I had intended to talk about today.

But, in the course of this essay, I have discovered that I don’t need to talk about those tedious and unimportant things. What matters really depends on what you, Dear Reader, got from this post. The ultimate McGuffin is in your hands. Be careful what you do with it. I believe neither of us is really ready to drop dead.

Leave a comment

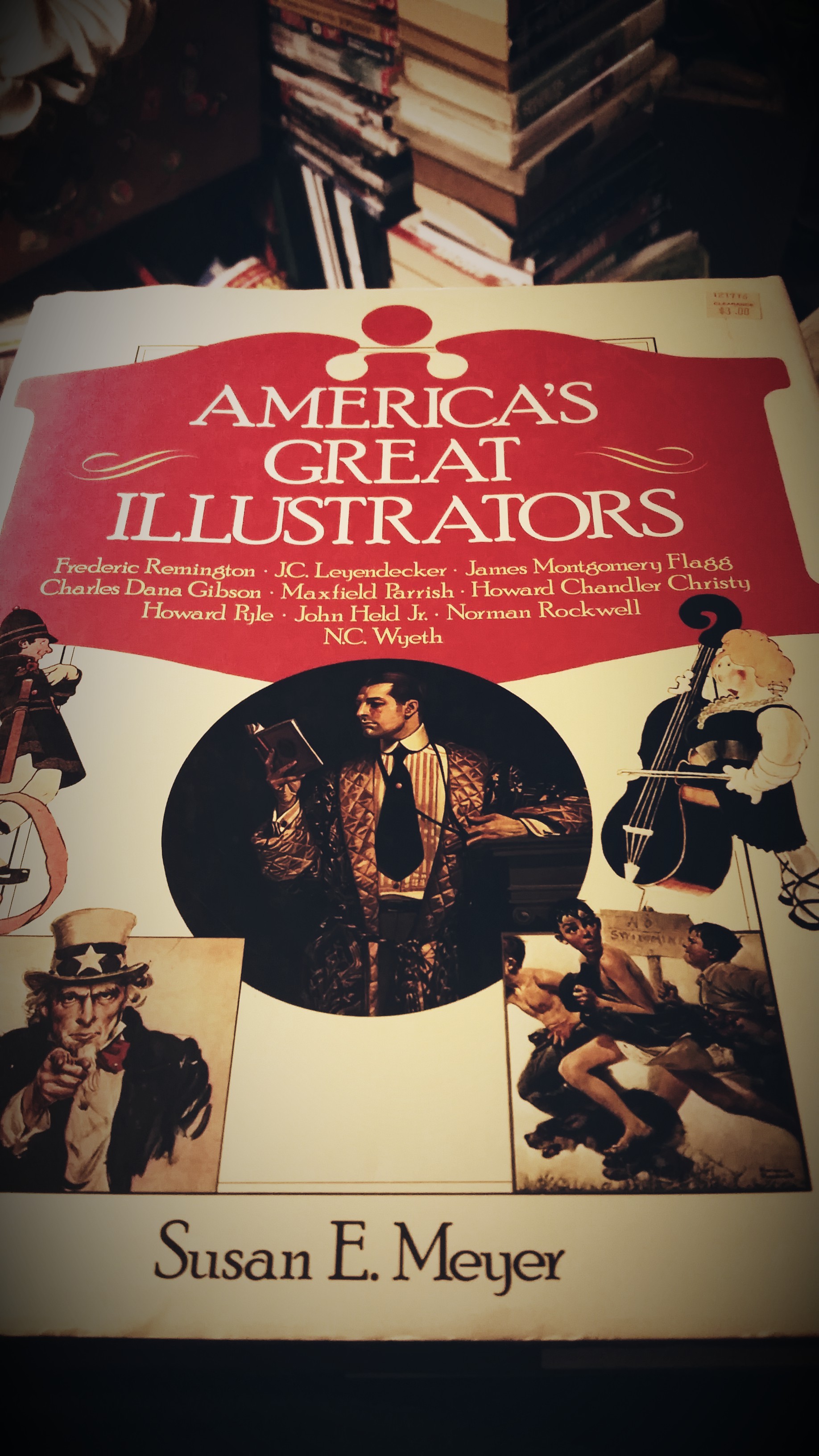

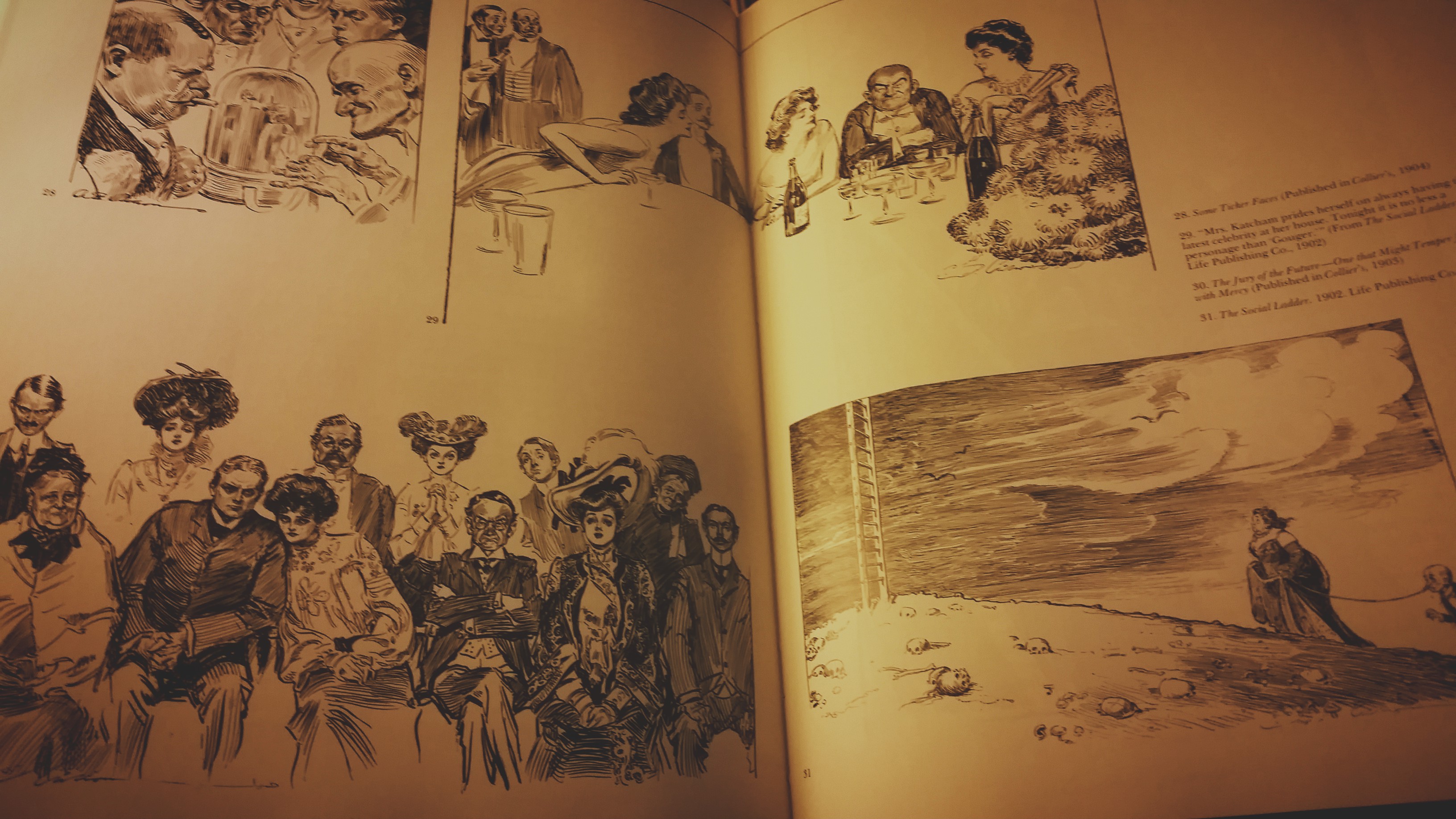

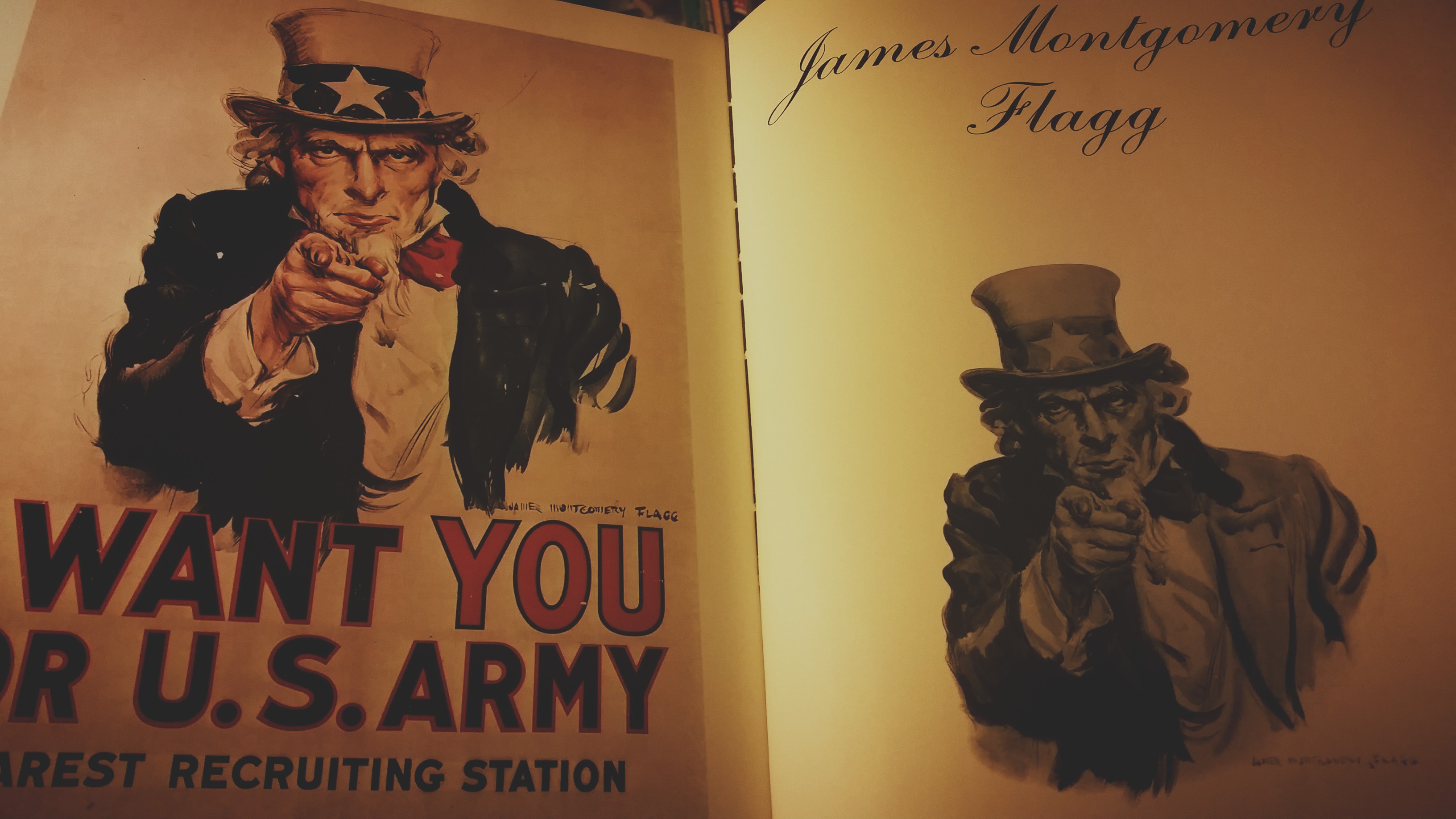

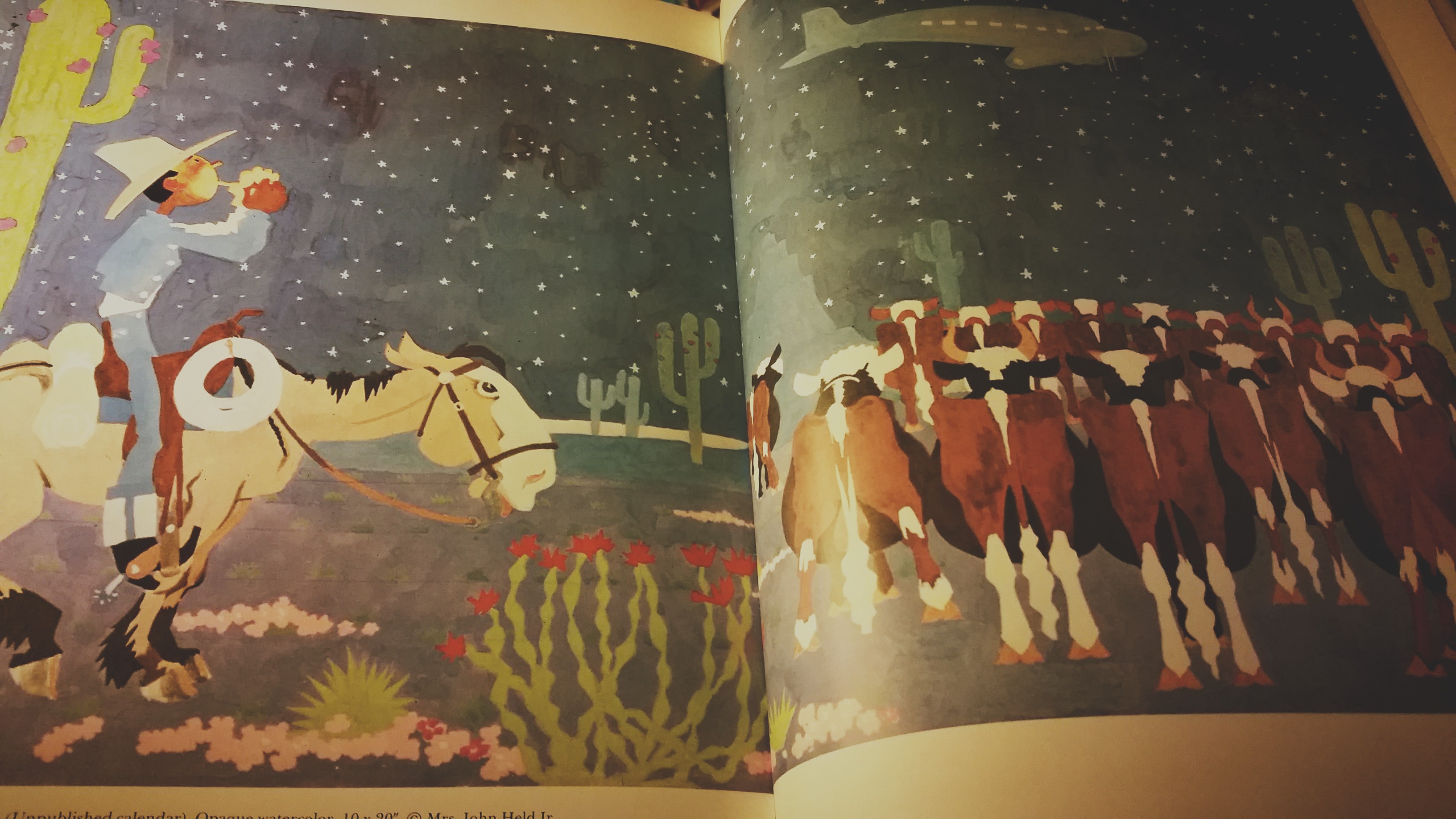

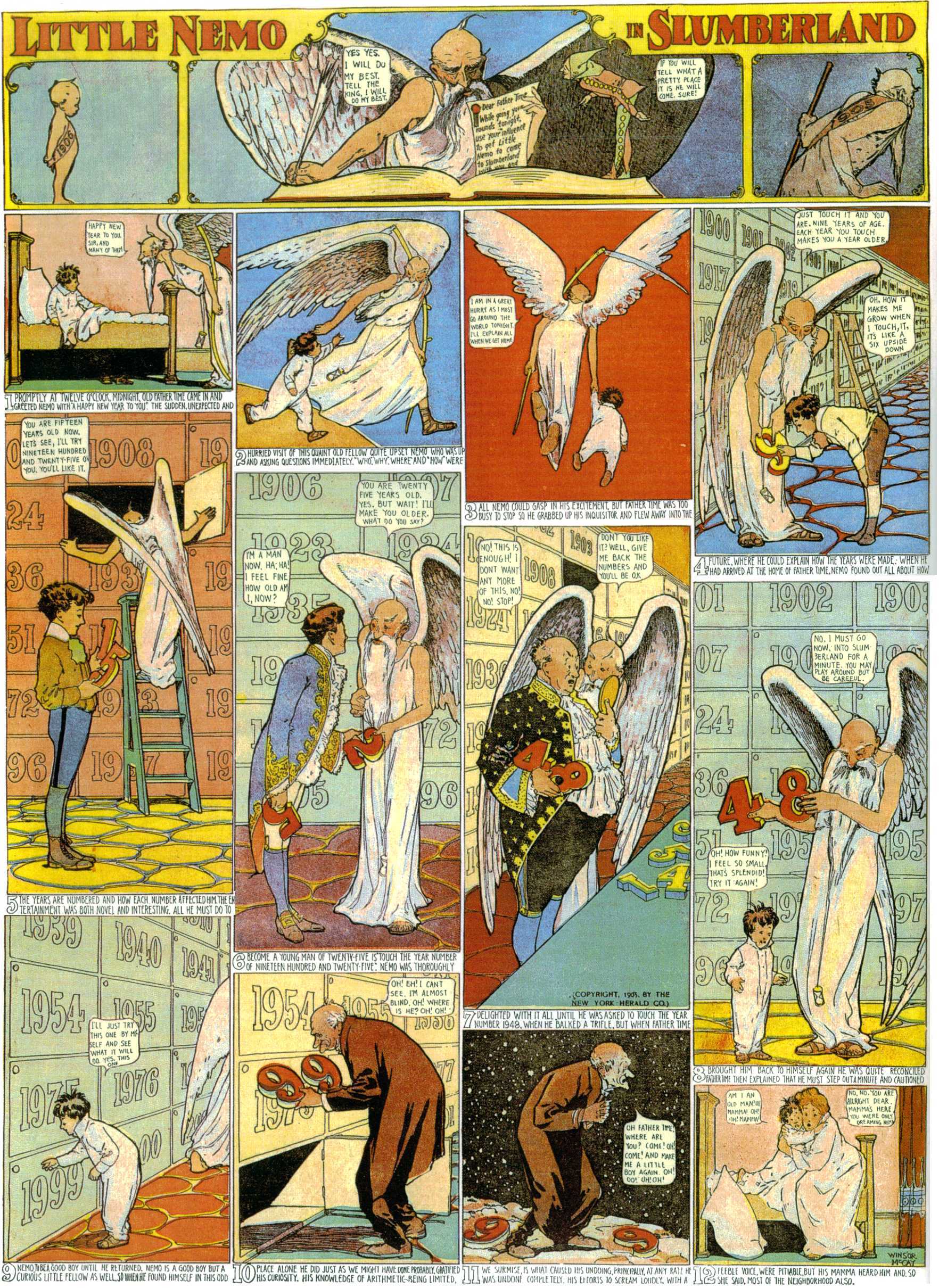

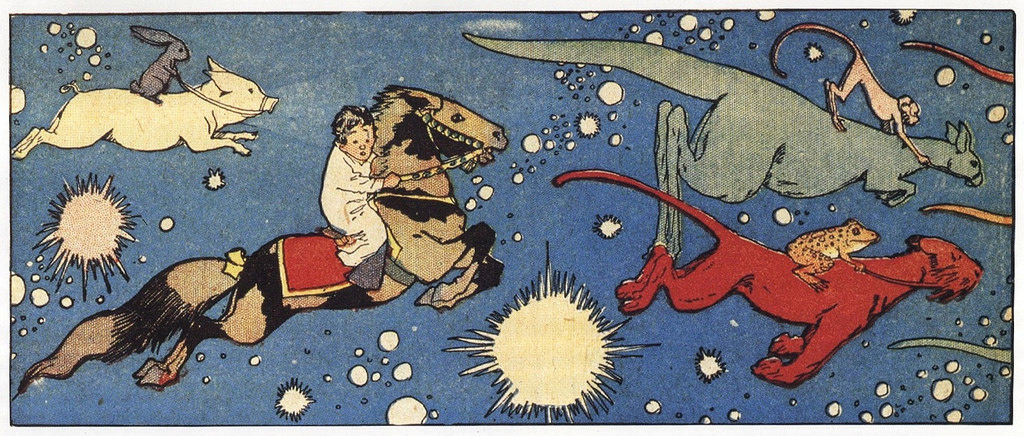

Filed under book review, commentary, humor, illustrations, novel writing, Paffooney, publishing, reading, strange and wonderful ideas about life, writing

Tagged as book review, book reviews, book-blog, books, reading, writing