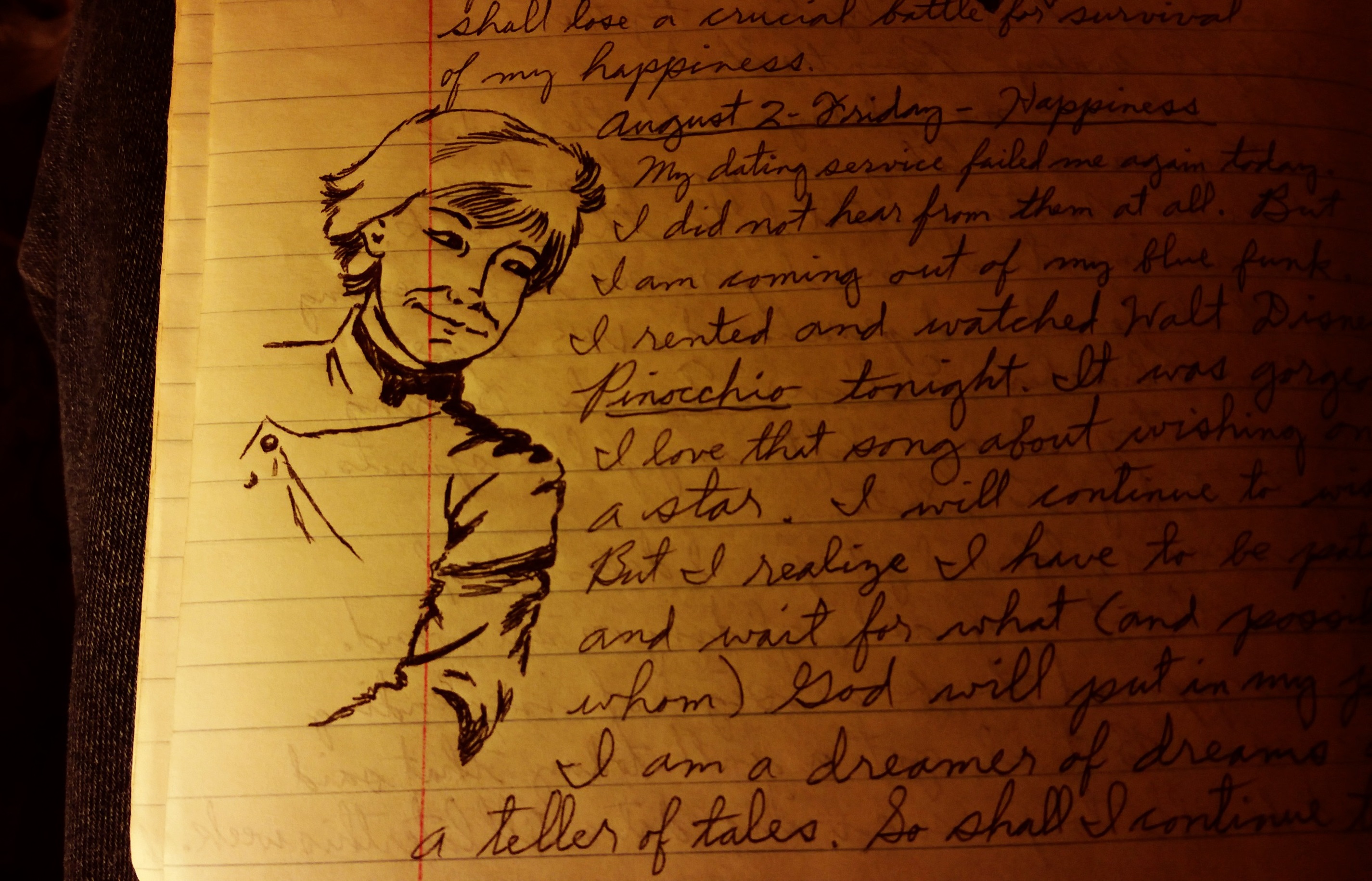

From the time I could first remember, I was always surrounded by stories. I had significantly gifted story-tellers in my life. My Grandpa Aldrich (Mom’s Dad) could spin a yarn about Dolly O’Rourke and her husband, Shorty the Dwarf, that would leave everybody in stitches. (Metaphorical, not Literal)

And my Grandma Beyer (Dad’s Mom) taught me about family history. She told me the story of how my great-uncle, her brother, died in a Navy training accident during World War II. He was in a gun turret aboard a destroyer when something went wrong, killing three in the explosion.

Words have power. They can connect you to people who died before you were ever born. They have the power to make you laugh or make you cry.

Are you reading my words now? After you have read them, they will be “read.” Take away the “a” and they will change color. They will be “red.” Did you see that trick coming? Especially since I telegraphed it with the colored picture that, if you are a normal reader, you read the “red” right before I connected it to “reading.”

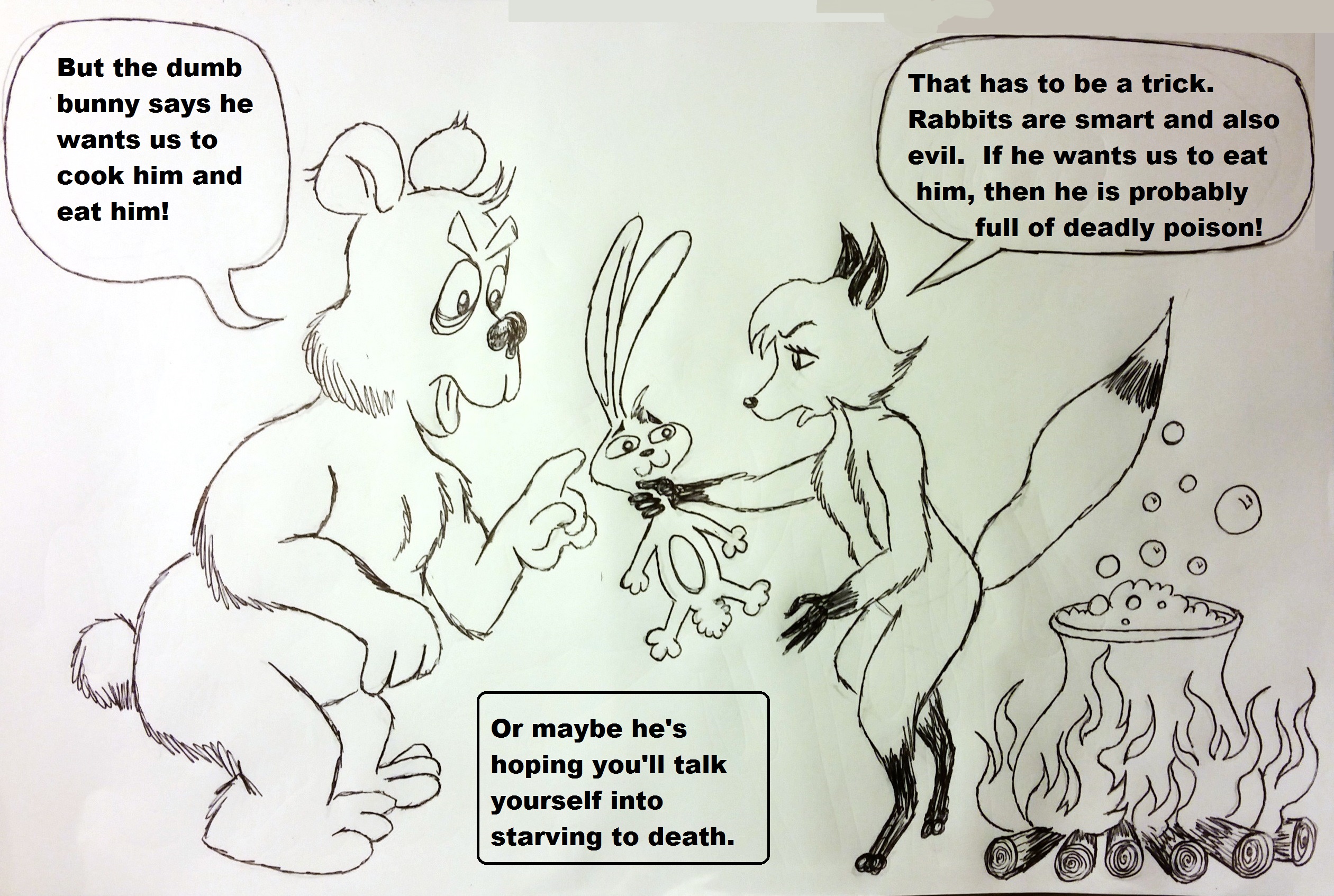

Comedy, the writing of things that can be (can bee, can dee, candee, candy) funny, is a magical sort of word wrangling that is neither fattening nor a threat to diabetes if you consume it. How many word tricks are in the previous sentence? I count 8. But that wholly depends on which “previous sentence” I meant. I didn’t say, “the sentence previous to this one.” There were thirteen sentences previous to that one (including the one in the picture) and “previous” simply means “coming before.” Of course, if it doesn’t simply mean that, remember, lying is also a word trick.

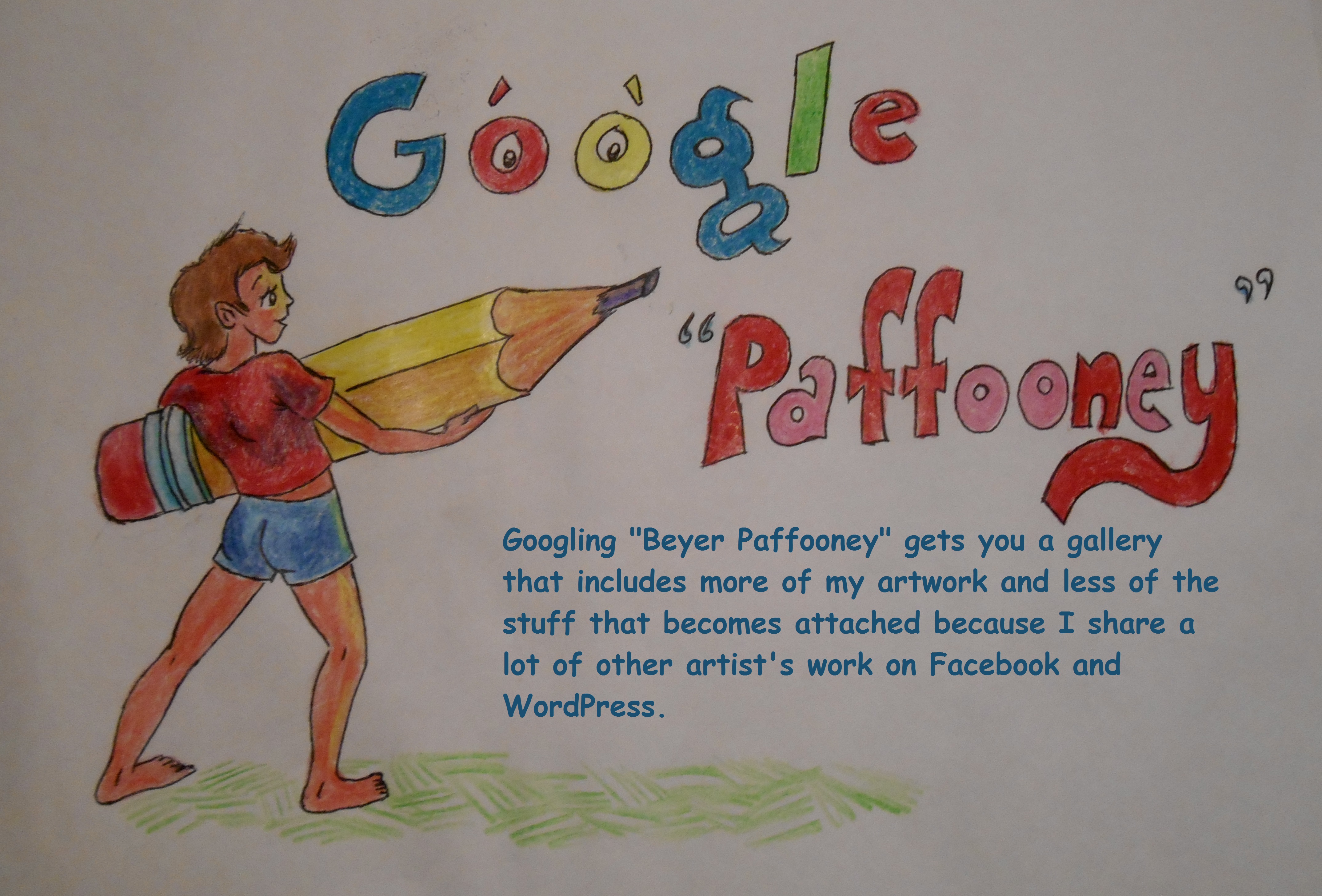

Here’s a magic word I created myself. It was a made-up word. But do a Google picture search on that word and see if you can avoid artwork by Mickey. And you should always pay attention to the small print.

So, now you see how it is. Words have magic. Real magic. If you know how to use them. And it is not always a matter of morphological prestidigitation like this post is full of. It can be the ordinary magic of a good sentence or a well-crafted paragraph. But it is a wizardry because it takes practice, and reading, and more practice, and arcane theories spoken in the back of old bookshops, and more practice. But anyone can do it. At least… anyone literate. Because the magic doesn’t exist without a reader. So, thank you for being gullible enough for me to enchant you today.

How To Write A Mickian Essay

I know the last thing you would ever consider doing is to take up writing essays like these. What kind of a moronic bingo-boingo clown wants to take everything he or she knows, put it in a high-speed blender and turn it all into idea milkshakes?

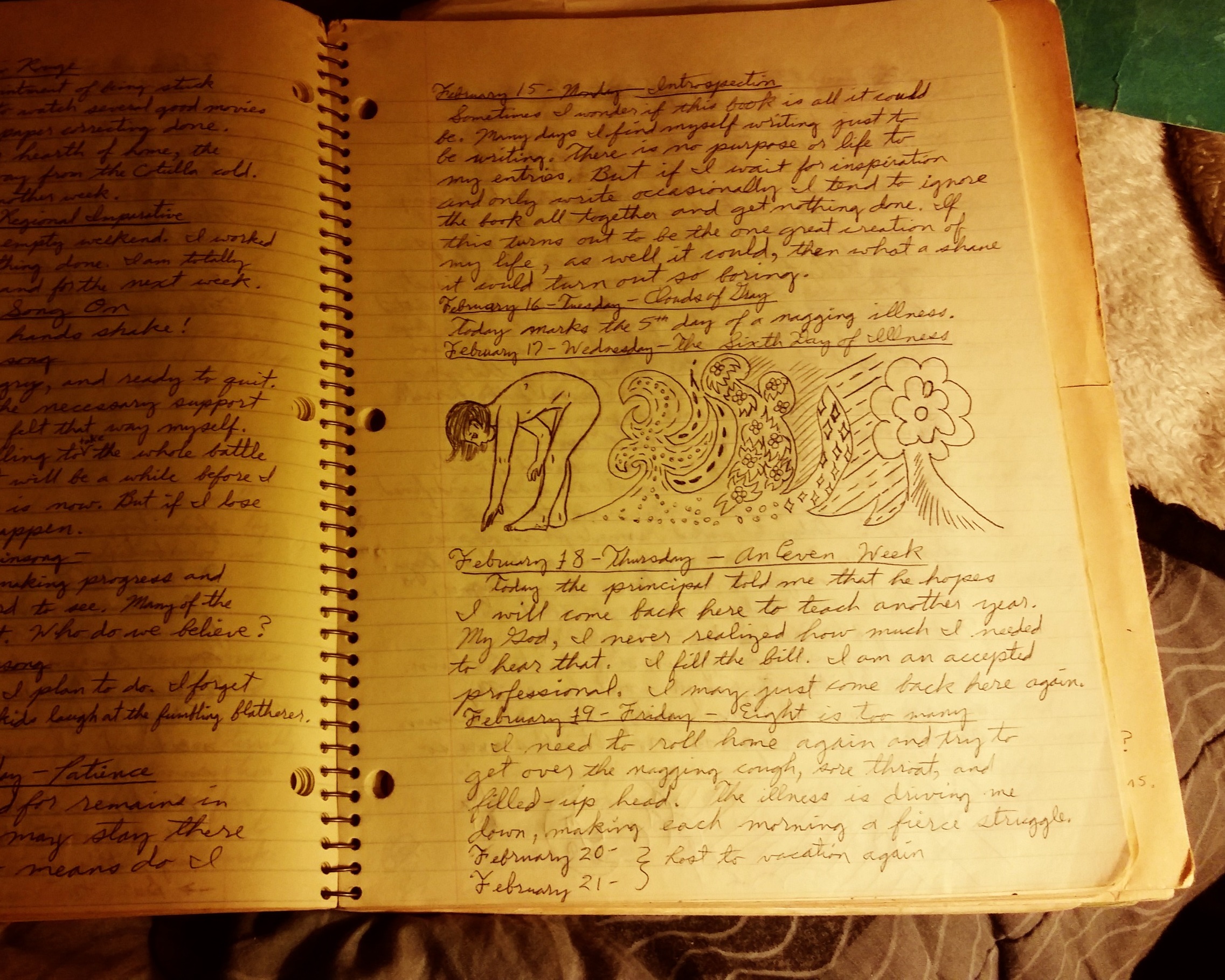

But I was a writing teacher for many years. And now, being retired and having no students to yell at when my blood pressure gets high, the urge to teach it again is overwhelming.

So, here goes…

Once you have picked the silly, pointless, or semi-obnoxious idea you want to shape the essay around, you have to write a lead. A lead is the attention-grabbing device or booby-trap for readers that will draw them into your essay. In a Mickian essay, whose purpose is to entertain, or possibly bore you in a mildly amusing manner, or cause you enough brain damage to make you want to send me money (this last possibility never seems to work, but I thought I’d throw it in there just in case), the lead is usually a “surpriser”, something so amazingly dumb or off-the-wall crazy that you just have to read, at least a little bit, to find out if this writer is really that insane or what. The rest of the intro paragraph that is not part of the lead may be used to draw things together to suggest the essay is not simply a chaotic mass of silly words in random order. It can point the reader down the jungle path that he or she can take to come out of the other end of the essay alive.

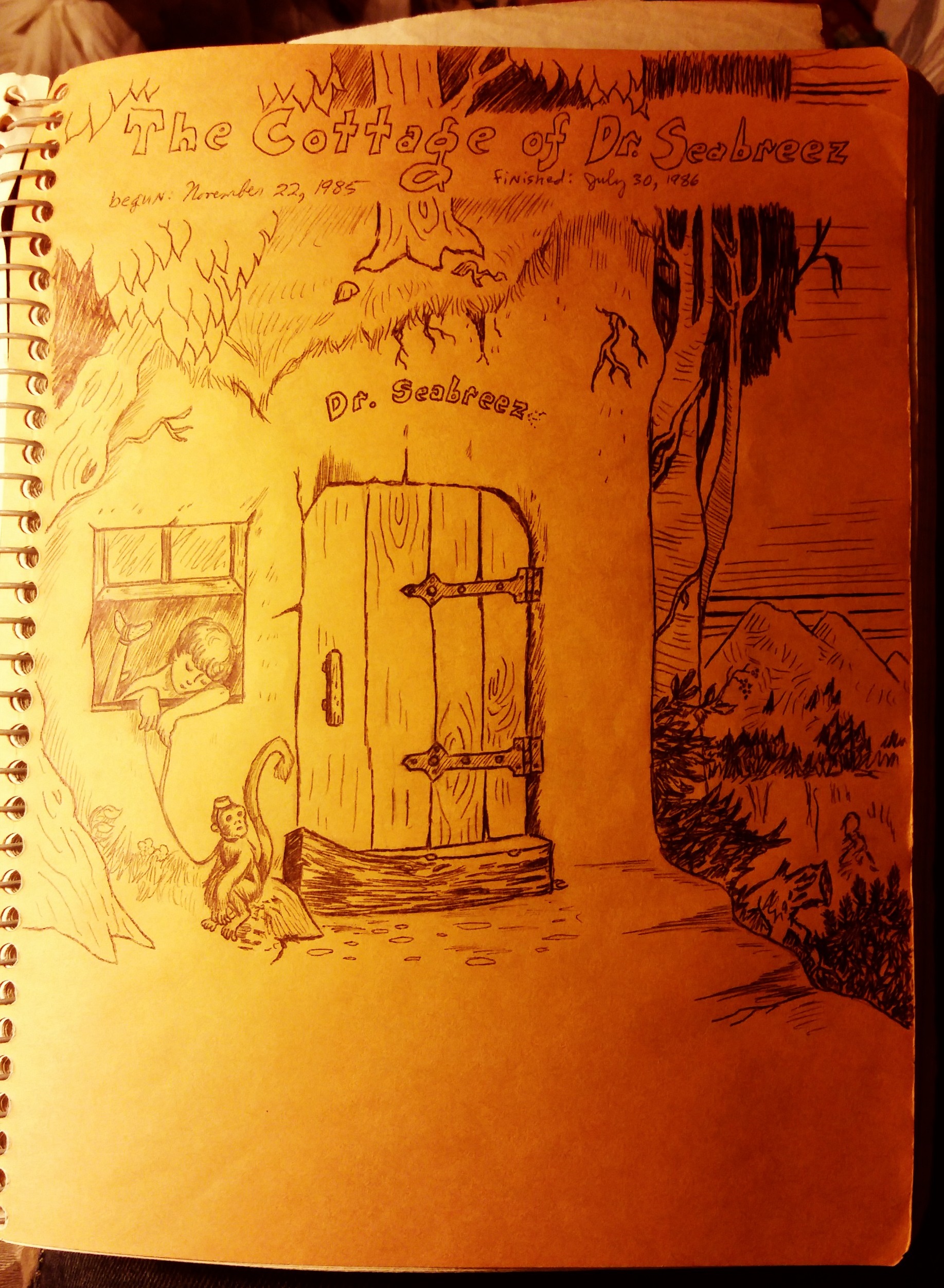

Once started on this insane quest to build an essay that will strangle the senses and mix up the mind of the reader, you have to carry out the plan in three or four body paragraphs. This is where you have to use those bricks of brainiac bull-puckie that you have saved up to be the concrete details in the framework of the main rooms of the little idea-house you are constructing. If you were to number or label these main rooms, this one you are reading now would, for example, be Room #2, or B, or “the second body paragraph”. And as you read this paragraph, you should be thinking in the voice of your favorite English teacher of all time. The three main rooms in this example idea house are beginning, middle, and end. You could also call them introduction, body, and conclusion. These are the rooms of your idea house that the reader will live in during his or her brief stay (assuming they don’t run out of the house screaming after seeing the clutter in the entryway).

The last thing you have to do is the concluding paragraph. (Of course, you have to realize that we are not actually there yet in this essay. This is Room C in the smelly chickenhouse of this essay, the third body paragraph.) The escape hatch on the essay that may potentially explode into fireworks of thoughts, daydreams, or plans for something better to do with your life than a read an essay written by an insane former middle school English teacher at any moment, is a necessary part of the whole process. This is where you have to remind them of what the essay is basically about, and leave them with the thought that you want to haunt them in their nightmares later. The last thing that you say in the essay is the thing they are the most likely to remember. So you need to save the best for last.

So, here, finally, is the exit door to this masterfully mixed-up Mickian Essay. It is a simple, and straightforward structure. The introduction containing the lead is followed by three or four body paragraphs that develop the idea and end in a conclusion that summarizes or simply restates the overall main idea. And now you know why all of my former students either know how to construct an essay, or have several years left in therapy sessions with a psychiatrist.

Leave a comment

Filed under commentary, education, humor, Paffooney, teaching, writing, writing teacher

Tagged as academic-writing, education, essay, essay writing, essays, foolish ideas, How to write an essay, humor, memoir, Mickian essays, teaching writing, teaching writing with humor, writing