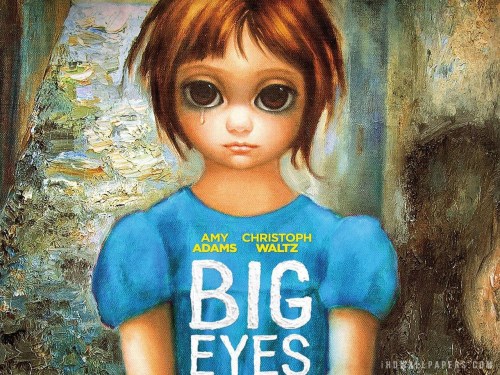

Yesterday, before the big game, I watched the DVD I bought of Tim Burton’s Golden Globe Award movie, Big Eyes. It is the true-story bio-pic of an artist I loved as a kid, Margaret Keane… though I knew her as Walter Keane.

Yesterday, before the big game, I watched the DVD I bought of Tim Burton’s Golden Globe Award movie, Big Eyes. It is the true-story bio-pic of an artist I loved as a kid, Margaret Keane… though I knew her as Walter Keane.

This movie is the bizarre real-life tale of an artist whose art was stolen from her by a man she loved, and supposedly loved her back. I have to wonder how you deal with a thing like that as an artist? I live in obscurity as an artist. My art has been published in several venues, but I have never been paid a dime for it. All I have ever gotten is publication in return for “exposure”, and limited exposure at that. But my art always brought vigor, joy, and light to my career as a school teacher. My art was always my own, and had either my own name on it, or the name Mickey on it. I shared my drawing skill in ways that directly impacted the lives of other people. It enriched my “teacher life”.

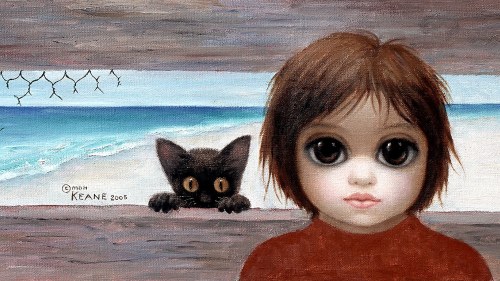

Mrs. Keane’s hauntingly beautiful big-eyed children appealed to the cartoonist in me. They expressed such deeply-felt character and emotion, that I was obsessed with imitating them. In fact, the “big-eye-ness” of them can still be detected in some of my work. I remember wondering how these children, mostly girls, could be drawn by a grown man. What was his obsession with little girls? But the true story reveals that he was a man so desperate to have art talent and notoriety that he put his name on his wife’s work, made her paint in secret, and eventually convinced himself that it was actually his. He had a real genius for marketing art, and he invented many of the art-market ploys that would later inform the careers of homely artists like Paul Detlafsen and Thomas Kinkaid. One wonders if Mrs. Keane could’ve ever become famous and popular without him.

The movie itself is a Tim Burton masterpiece that reveals the artist that lives within the filmmaker himself. I love Burton’s movies for their visual mastery and artistic atmosphere. They are all very different in look and feel. Batman was very dark and Gothic, inventing an entirely new way of seeing Batman that differed remarkably from the 60’s TV series. Edward Scissorhands was full of muted, pastel colors and gentle humor. Alice in Wonderland was full of bright colors and oddly distorted fantasy characters. Dark Shadows was Gothic melodrama in 70’s pop-art style. This movie was true to the paintings that inspired it and visually saturate it. It is beautiful and colorful, while also serious and somber. It makes you contemplate the tears in the eyes of the big-eyed waifs in so many of the pictures. It is a movie “I love with a love that is more than a love in this kingdom by the sea”… if I may get all obsessive like Edgar Allen Poe.

So, there you have it. Not so much a movie review as an effusion of love and admiration for an artist’s entire life and work. I am captivated… fascinated… addicted… all the things I always feel about works of great art.

Winsor McCay

One work of comic strip art stands alone as having earned the artist, Winsor McCay, a full-fledged exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. Little Nemo in Slumberland is a one-of-a-kind achievement in fantasy art.

Winsor McCay lived from his birth in Michigan in 1869 to his finale in Brooklyn in 1934. In that time he created volumes full of his fine-art pages of full-page color newspaper cartoons, most in the four-color process.

As a boy, he pursued art from very early on, before he was twenty creating paintings turned into advertising and circus posters. He spent his early manhood doing amazingly detailed half-page political cartoons built around the editorials of Arthur Brisbane, He then became a staff artist for the Cincinnati Times Star Newspaper, illustrating fires, accidents, meetings, and notable events. He worked in the newspaper business with American artists like Winslow Homer and Frederick Remington who also developed their art skills through newspaper illustration. He moved into newspaper comics with numerous series strips that included Dreams of the Rarebit Fiend and Little Nemo in Slumberland. And he followed that massive amount of work up by becoming the “Father of the Animated Cartoon” with Gertie the Dinosaur, with whom he toured the US giving public performances as illustrated in the silent film below;

The truly amazing thing about his great volume of work was the intricate detail of every single panel and page. It represents a fantastic amount of work hours poured into the creation of art with an intense love of drawing. You can see in the many pages of Little Nemo how great he was as a draftsman, doing architectural renderings that rivaled any gifted architect. His fantasy artwork rendered the totally unbelievable and the creatively absurd in ways that made them completely believable.

I bought my copy of Nostalgia Press’s Little Nemo collection in the middle 70’s and have studied it more than the Bible in the intervening years. Winsor McCay taught me many art tricks and design flourishes that I still copy and steal to this very day.

No amount of negative criticism could ever change my faith in the talents of McCay. But since I have never seen a harsh word written against him, I have to think that problem will never come up.

My only regret is that the wonders of Winsor McCay, being over a hundred years old, will not be appreciated by a more modern generation to whom these glorious cartoon artworks are not generally available.

2 Comments

Filed under art my Grandpa loved, artists I admire, artwork, book review, cartoon review, cartoons, comic strips, commentary

Tagged as Little Nemo in Slumberland, Winsor McCay