My bloodwork first revealed my diabetes in the Summer of 2000. So, the first of my two grateful notations is my diabetes. Surprise you, does it? There are very good reasons why this bad thing that happened to me has helped me more in life than some of the things most people identify as the best things in life.

Diabetes is a chemical nightmare that you fall into by a compounding of your worst daily habits. Your body turns food into a form that your blood carries to every cell in your body to provide the energy that every living cell runs on. But that form of chemical is glucose, a sugar. And sugar is not only the fuel for cellular life and activity, it is a poison.

Blood sugar is like highly combustible gasoline in an internal combustion engine. If you have too much gas causing too large of an explosion with every spark from the sparkplug, the longer you run it with your foot on the gas, the more likely you are to blow the engine up. This is the reason diabetes causes heart attacks, strokes, and can damage or destroy so many of your body’s essential organs.

The regulatory liquid that controls the sugar’s poison power is insulin. It is produced in the pancreas as a peptide hormone, a chemical that cooks and flavors the blood sugar to make it delicious enough to be more easily eaten up by the cells of the body. But sometimes the pancreas gets lazy or overworked enough to become rebellious and it stops producing enough insulin to cook the sugar. And sometimes, as in my case, the pancreas begins producing insulin who simply aren’t very good cooks. I have way too much insulin in my bloodstream, but it is wimpy and weak and couldn’t win a sugar cook-off if my life depended upon it. And my life does depend on it.

The reason I am grateful for diabetes is the plethora of fundamental life lessons that I had to learn in order to keep living a good life.

How well you can think and feel and move around depends on how well you manage what you eat.

Candy is out. If you like sweetness in your meals, natural fruit sugars like fructose, especially when combined with helpful, cancer-suppressing antioxidants like you find in strawberries, are a much better choice. Niacin is the name of a chemical you need to know when choosing what to eat. Niacin helps balance your blood sugar level, making your insulin gain levels in cooking skill chemically. You find niacin in foods like peanut butter, pork sausage, chicken wings, and mushrooms, as well as many other foods. For nearly twenty-one years, I have regulated my blood sugar successfully by making adjustments to my dietary habits.

And that leads to the other thing that I am grateful for. I am grateful for my ability to change my daily habits when necessary. I have learned that even deeply entrenched habits can be altered over time by small changes I make, noting them and constantly examining my progress. It has not only helped me navigate numerous health problems, but it has also aided me in completing my 5-year Chapter 13 bankruptcy. So, I am grateful for diabetes and changeable habits.

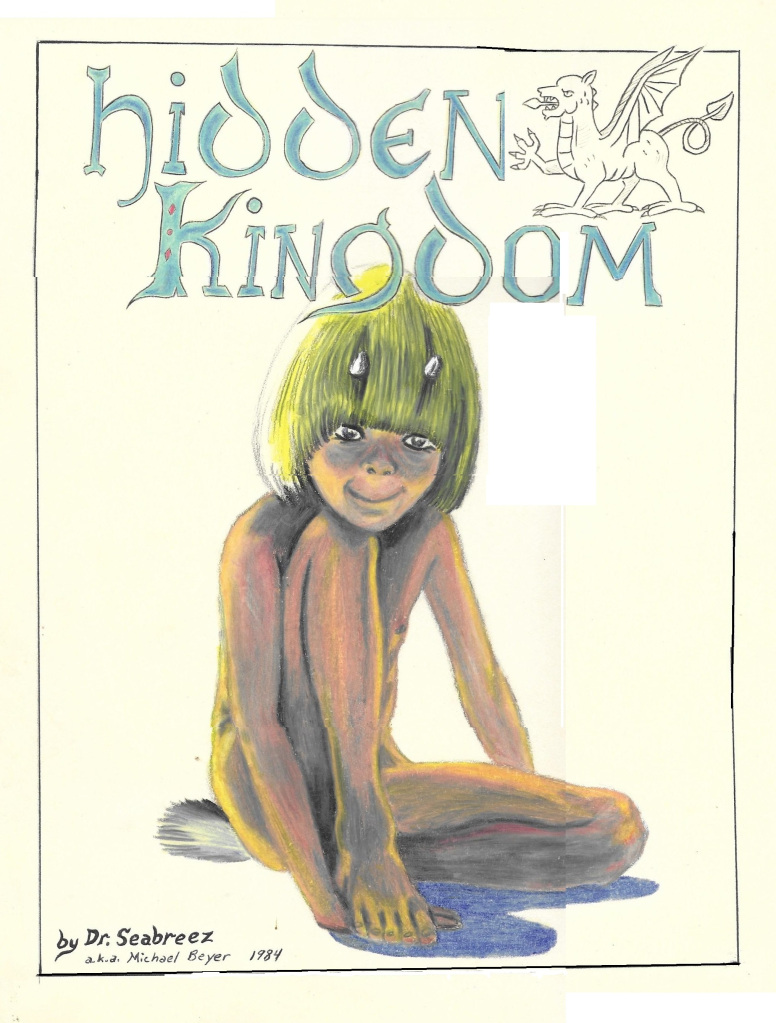

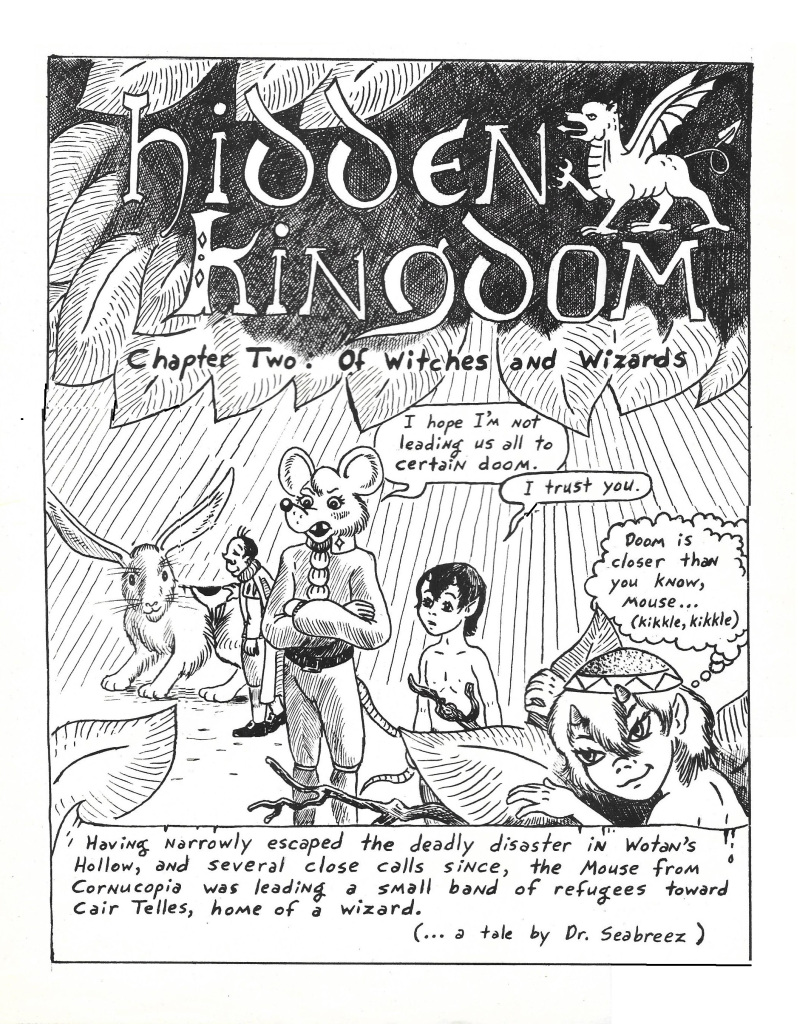

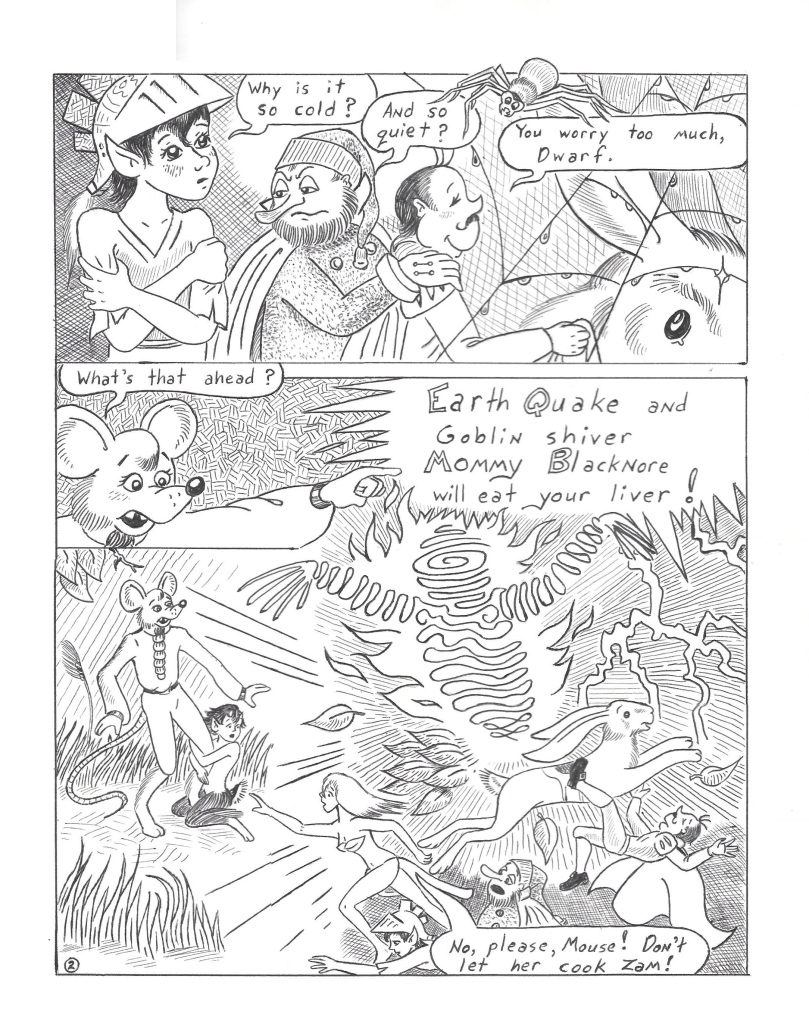

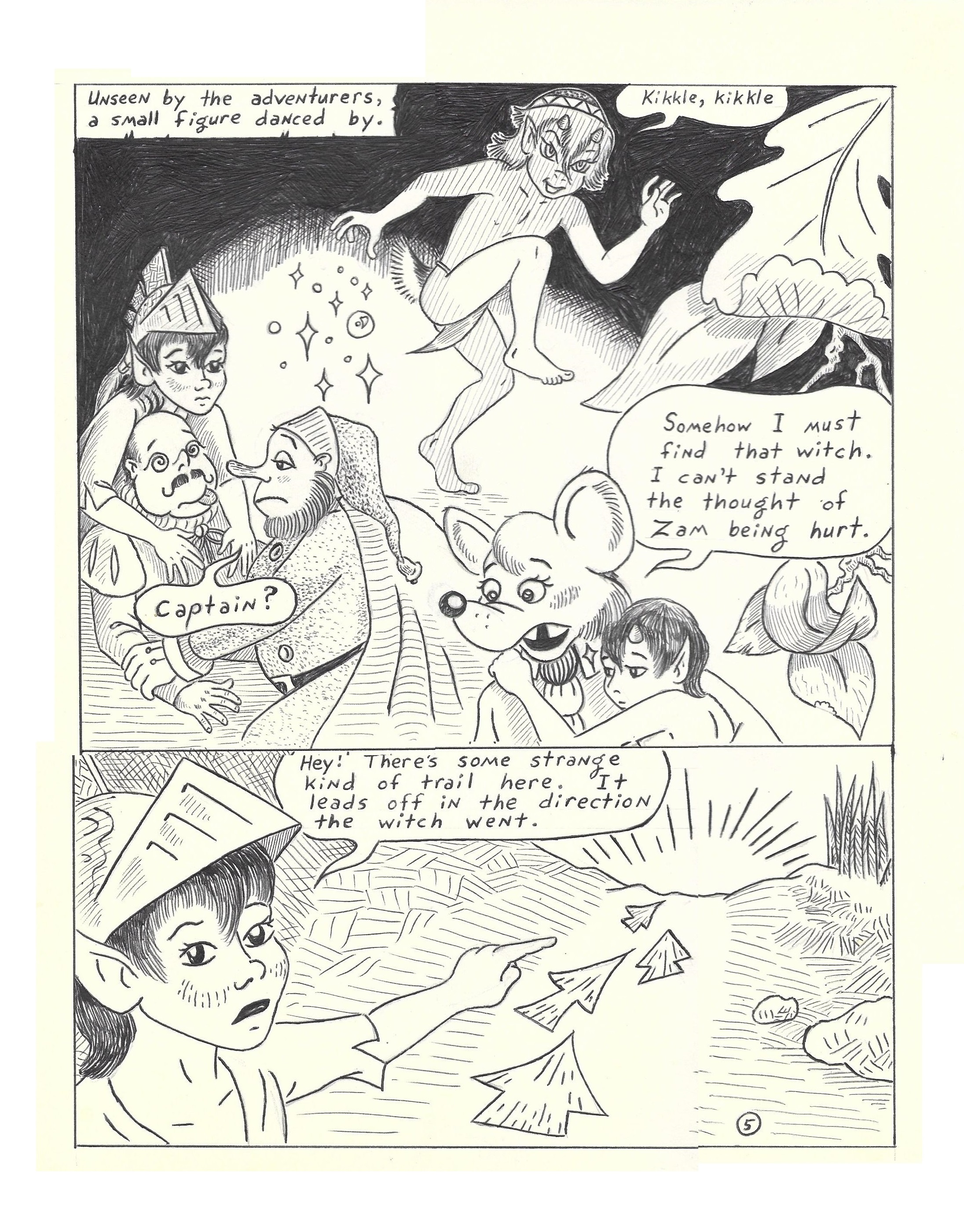

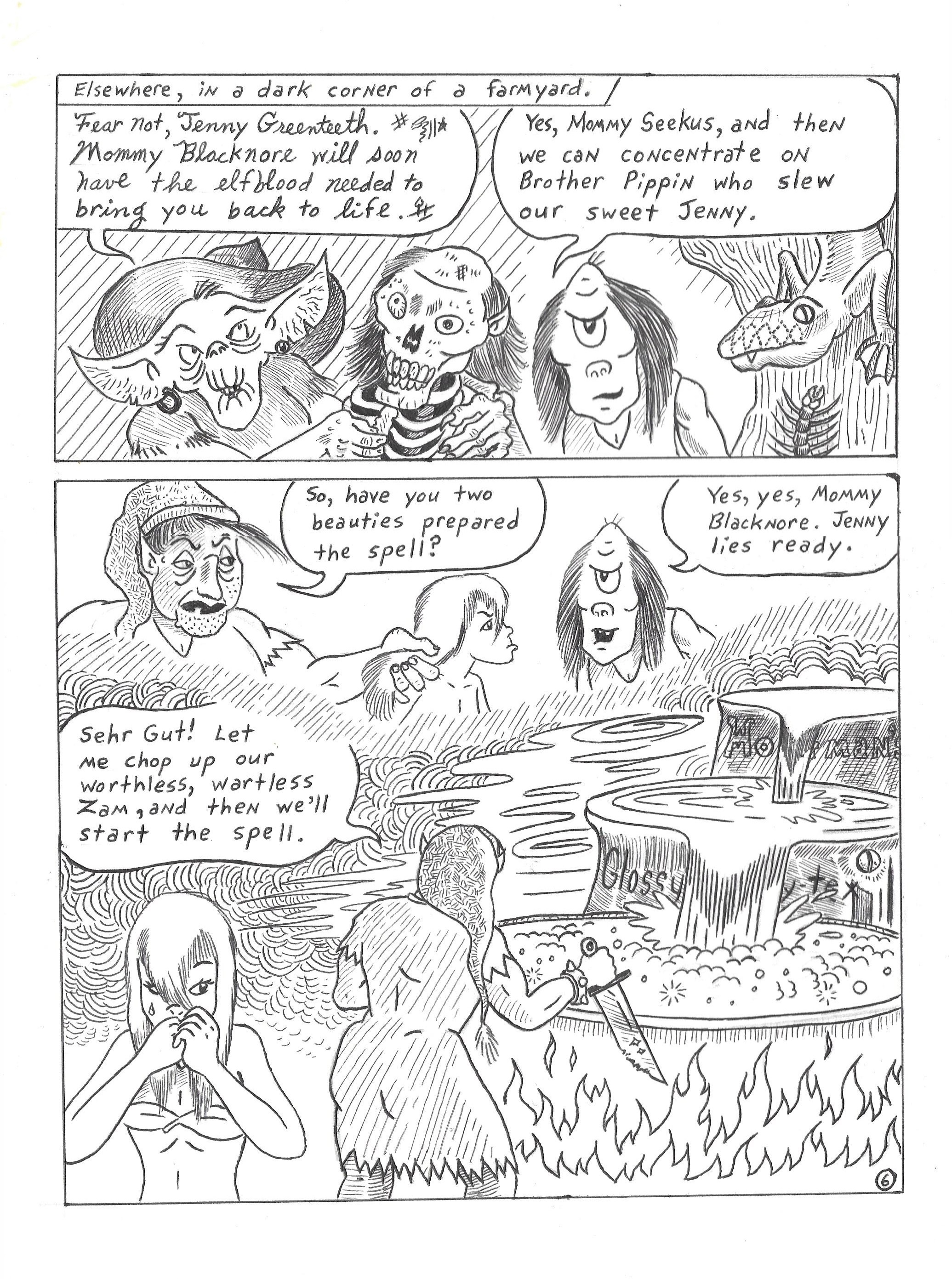

Mickey Being Mickey

A new day dawns. It leaves me wondering. Who am I today? Who will I be tomorrow?

The opportunity to have any sort of control over who and what I am is coming to a close. I don’t really know how much longer I have before pain and illness dissolve me into nothingness. But death is not the end of existence. I may be forgotten totally by the day after next Thursday, but my existence will still have become a permanent fact. Yes, I am one of those dopey-derfy-think-too-much types known as an existentialist.

I am feeling ill again. Any time that happens may be the last time. But that doesn’t worry me.

The important thing is that the dance continues. It doesn’t matter who the dancers are, or who supplies the music.

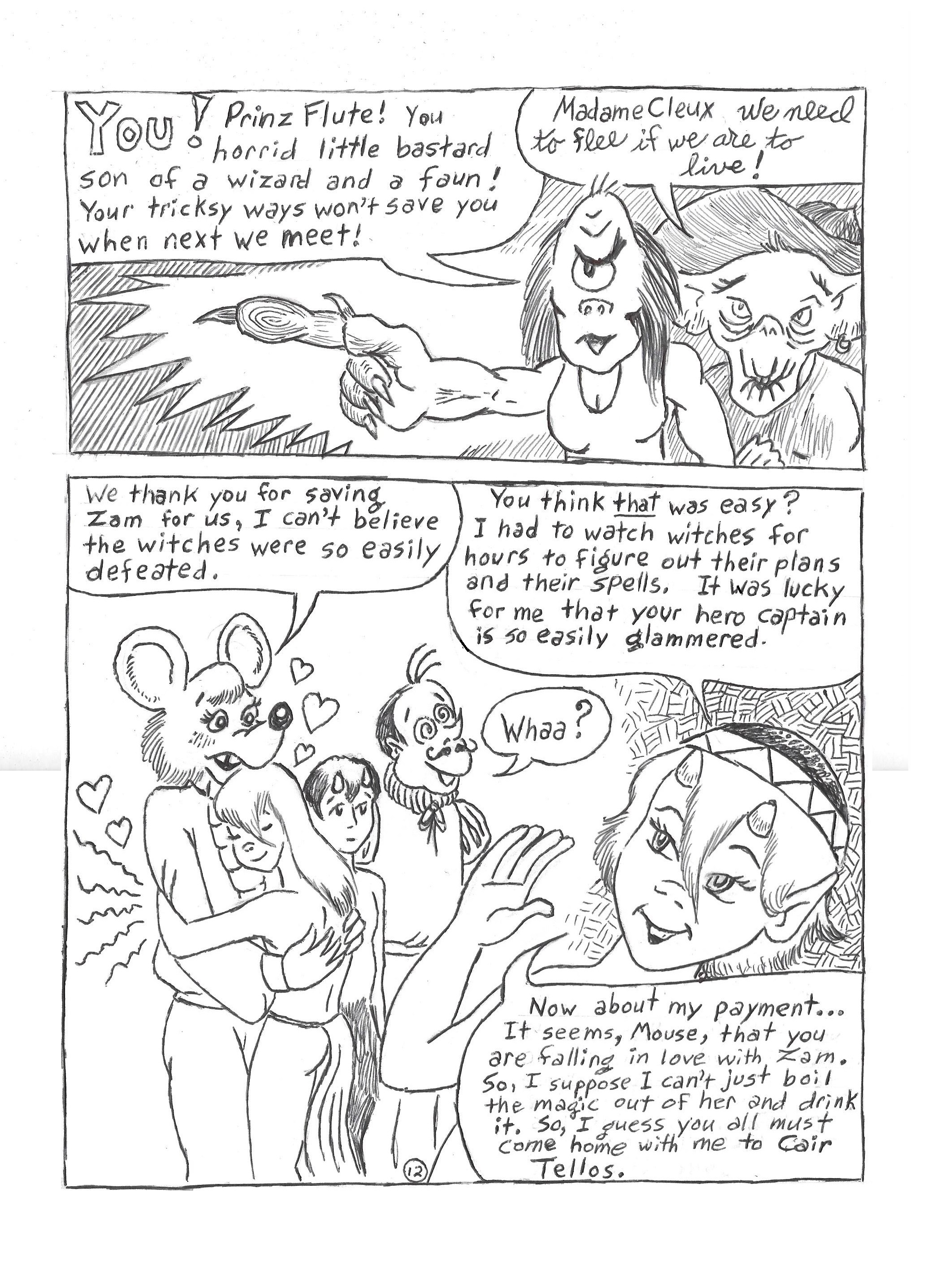

We can be clowns if we choose to be.

We can safely be fools if we really can’t help it.

An awful lot of awful things go into who and what we are. Those things make us full of awe. They make us awesome. Aw, shucks. What an awful thing to say.

But what is all this stuff and nonsense really about today?

It’s just Mickey being Mickey… Mickey for another day.

It’s not really poetry. It certainly isn’t wisdom. It’s a little bit funny, and only mildly depressing… for a change.

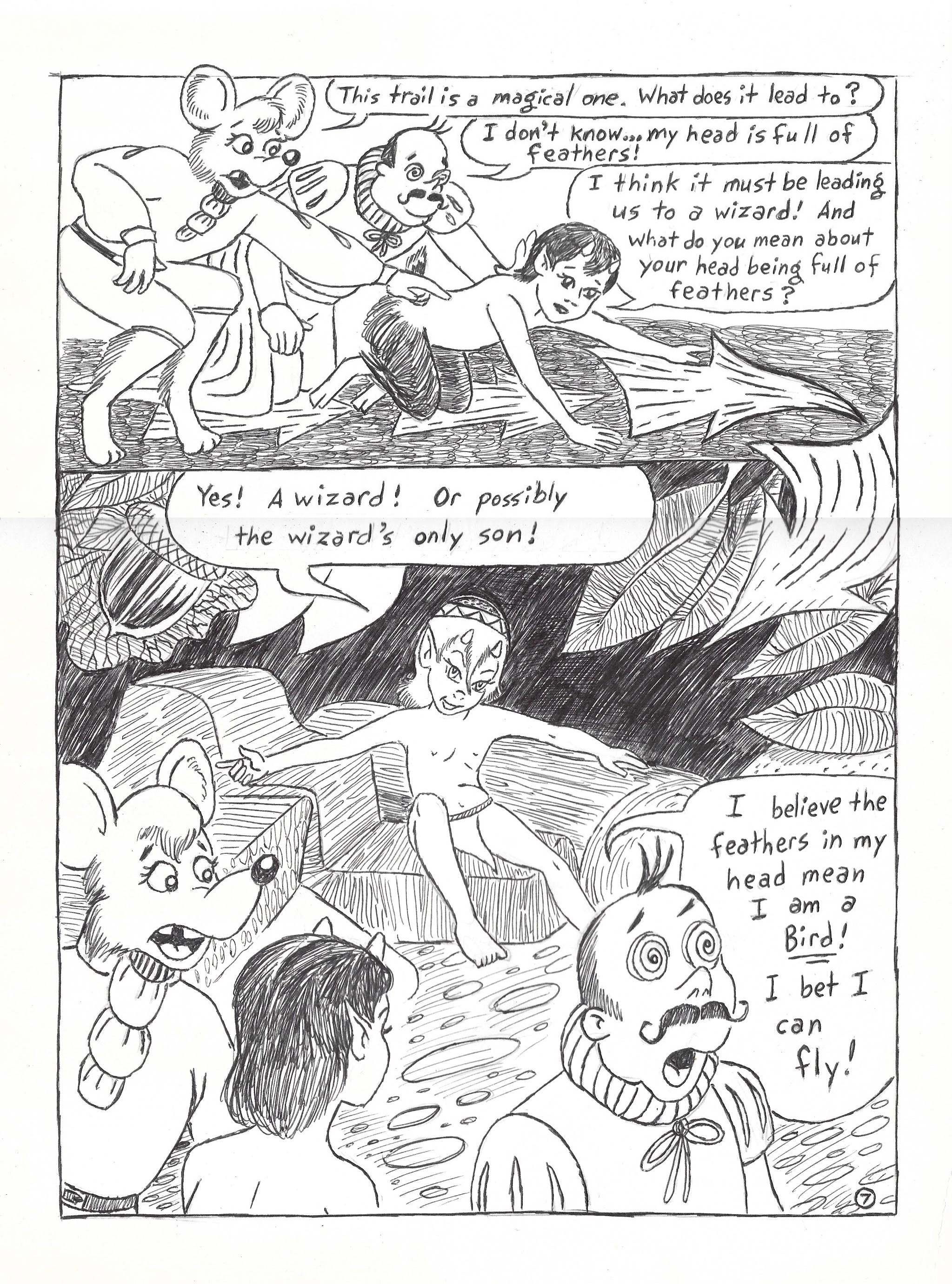

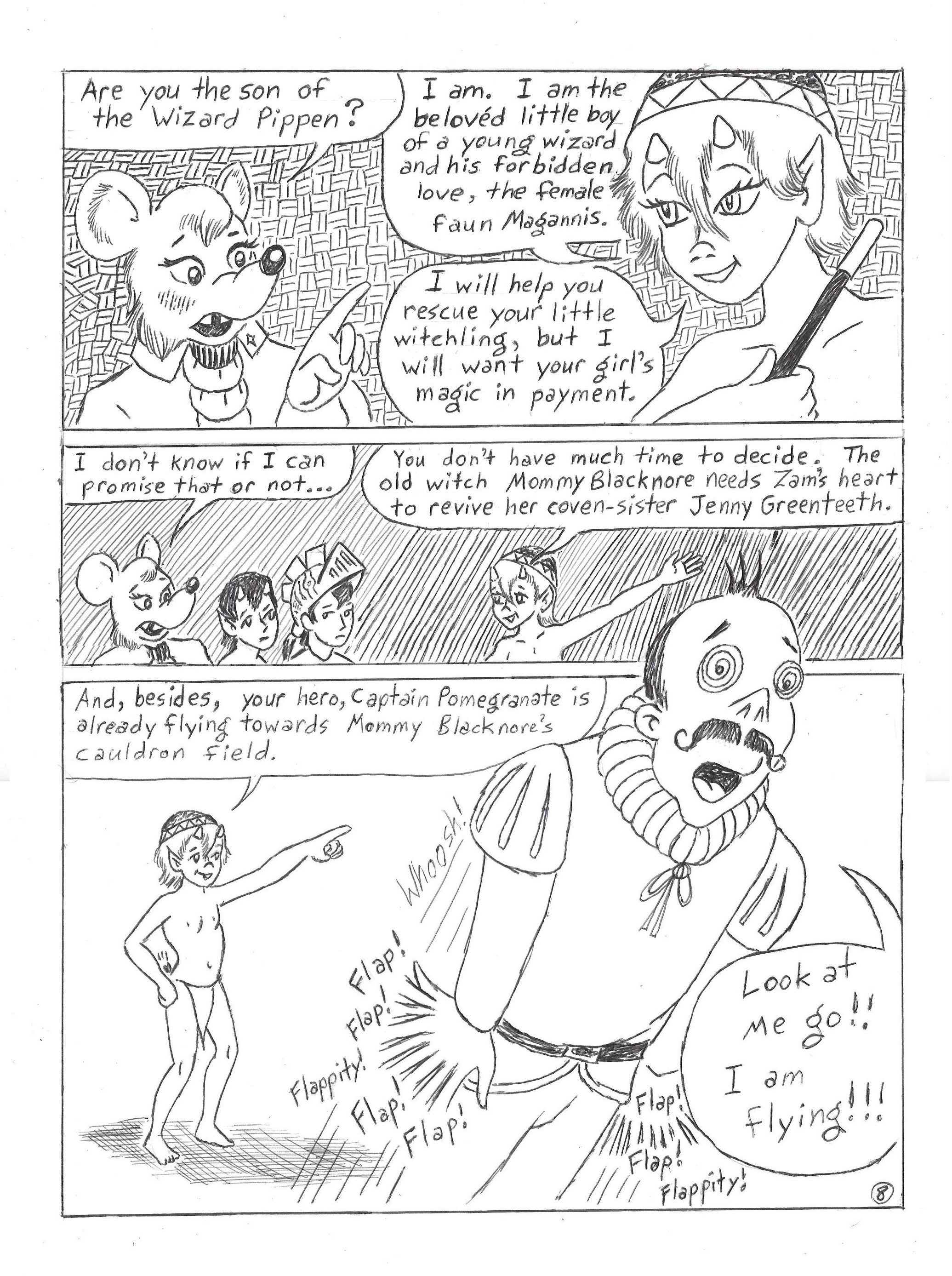

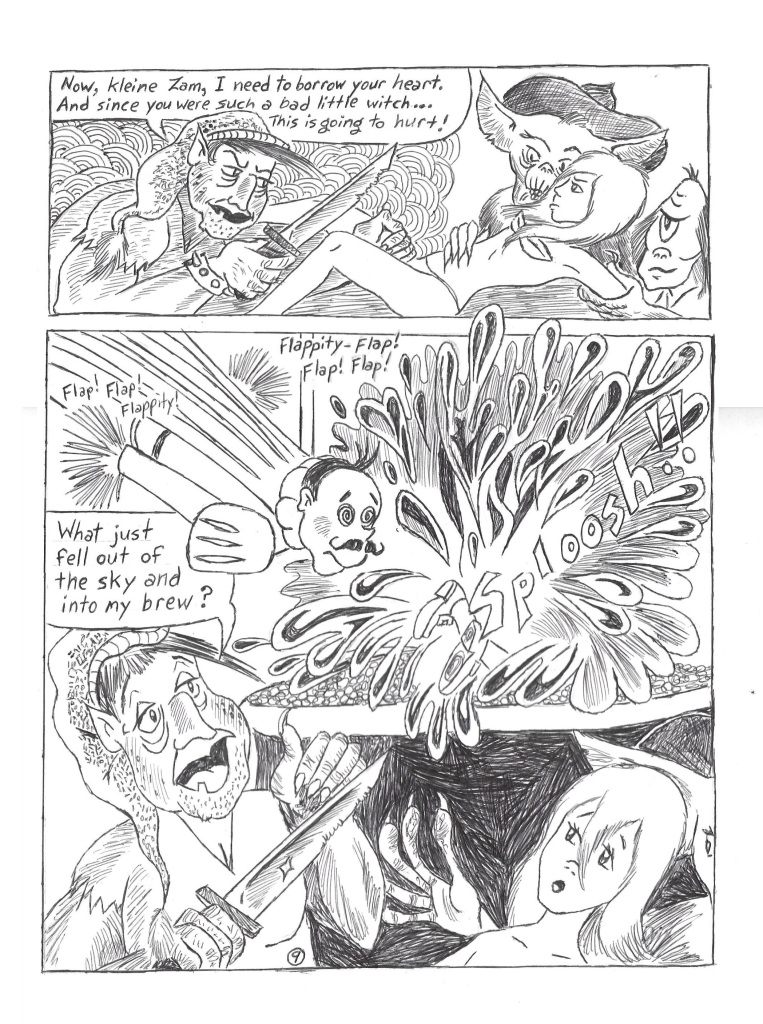

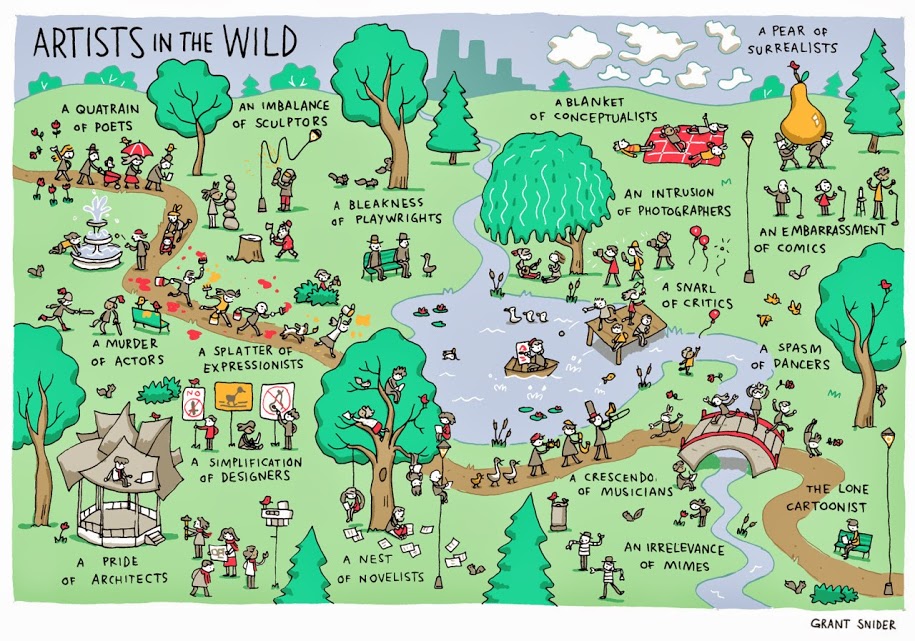

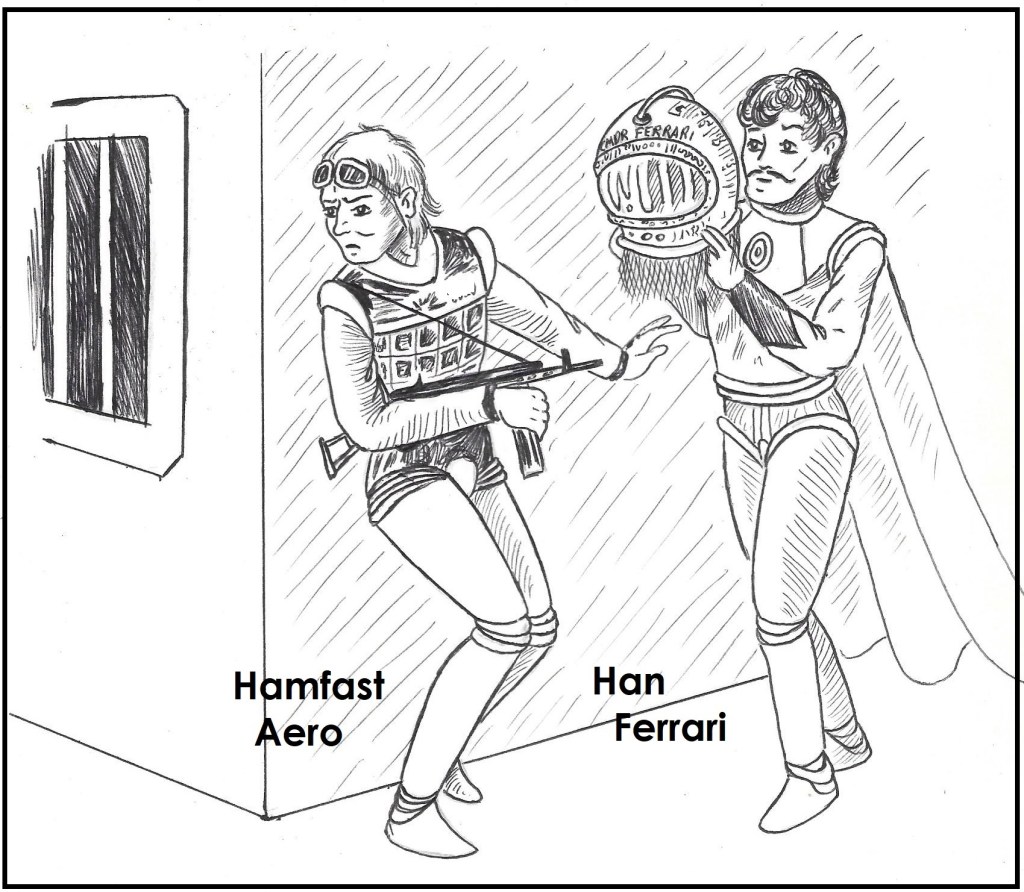

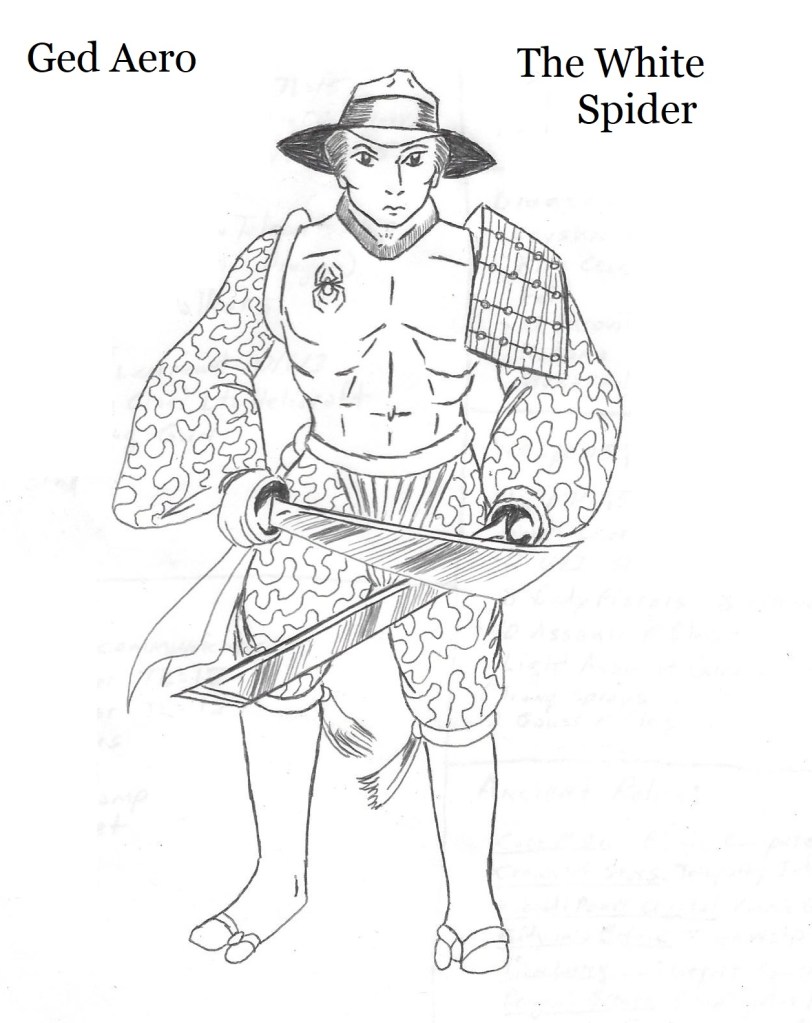

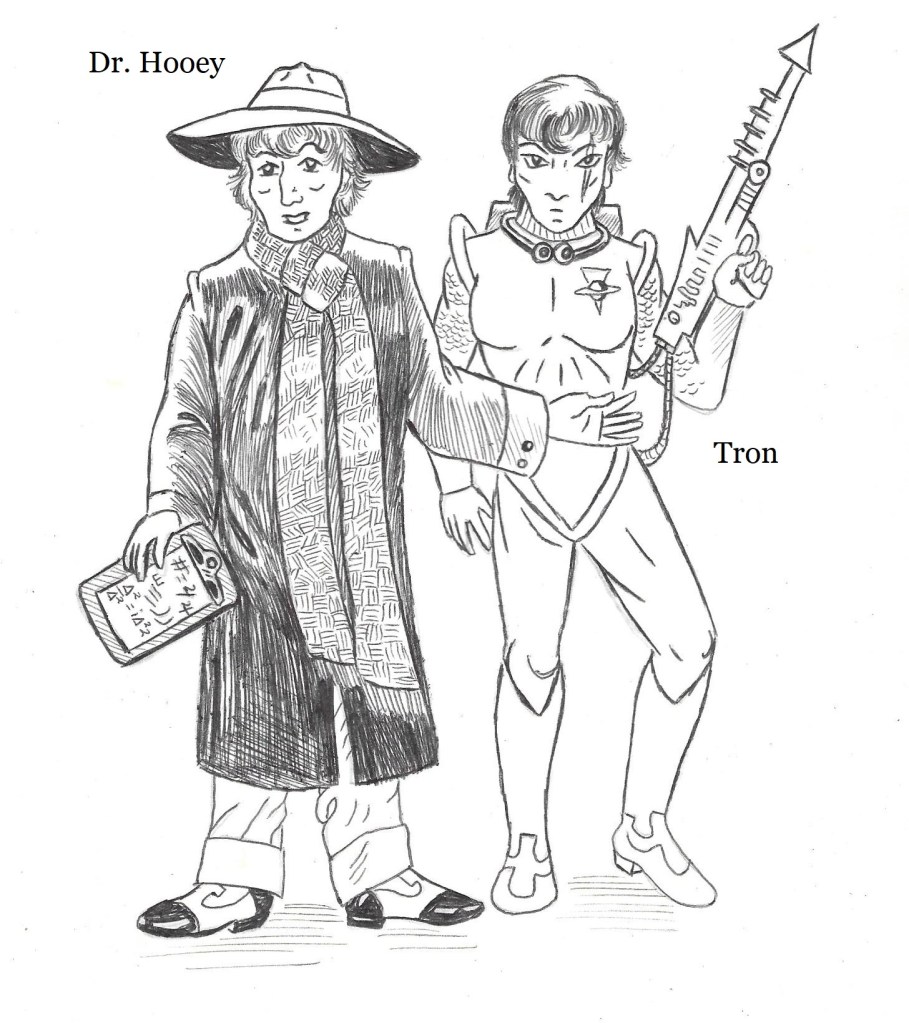

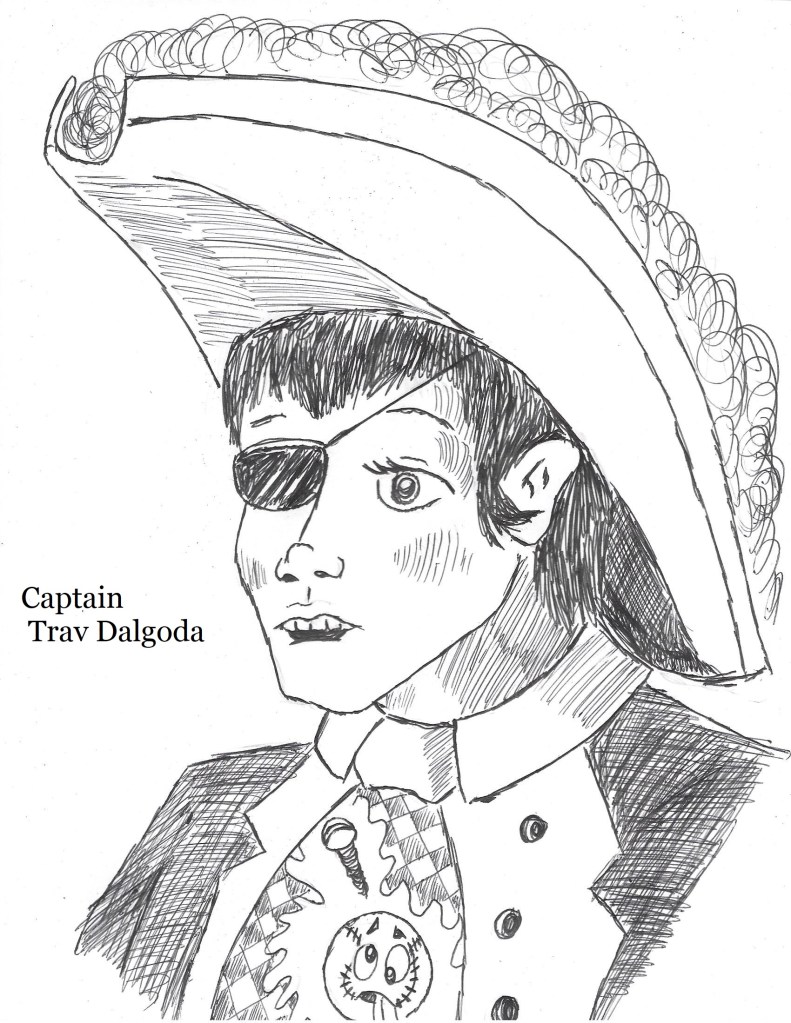

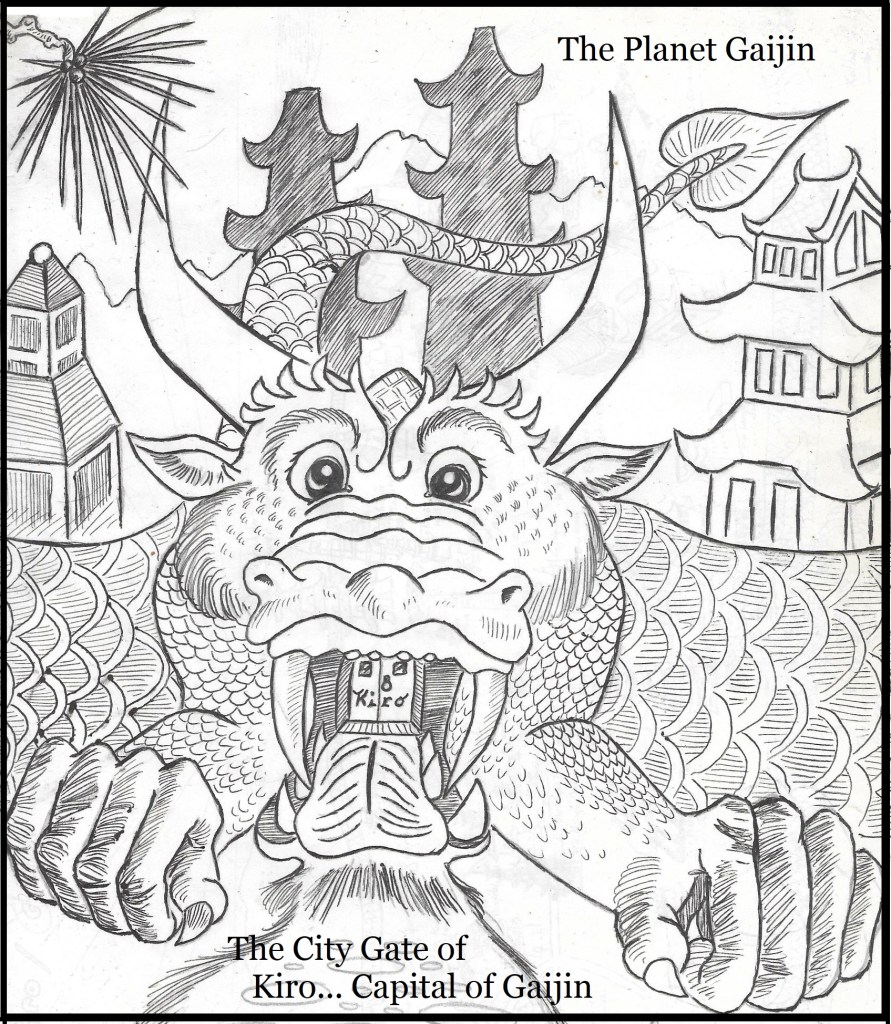

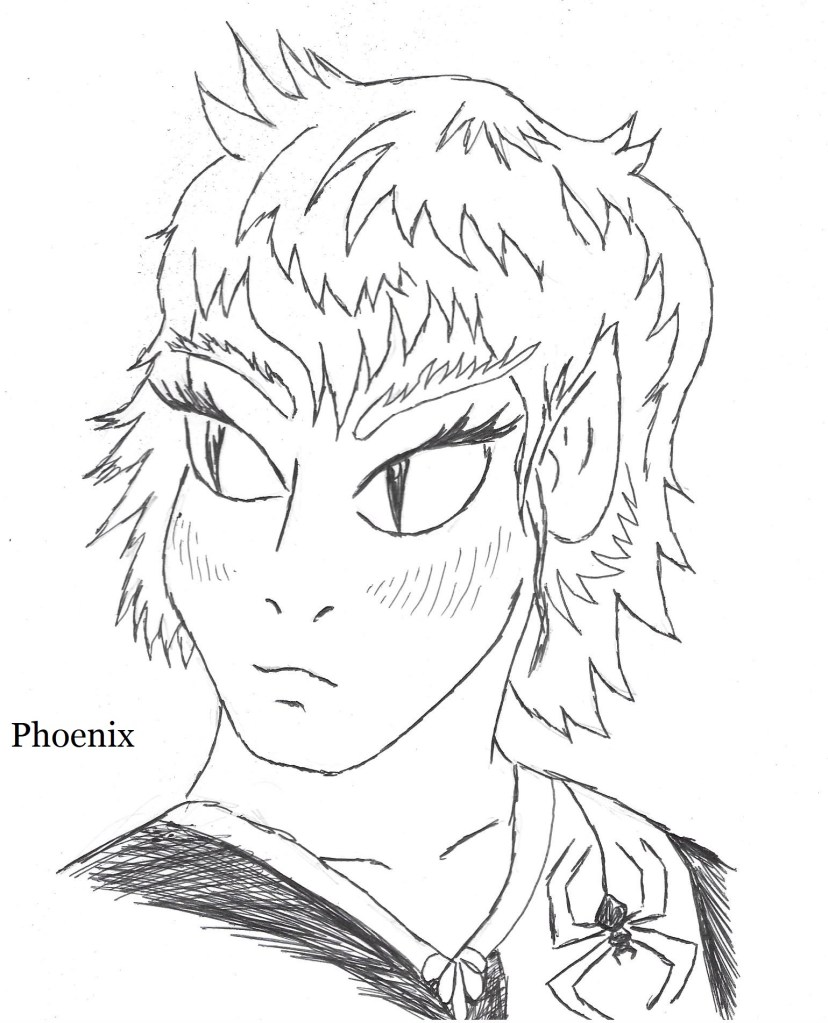

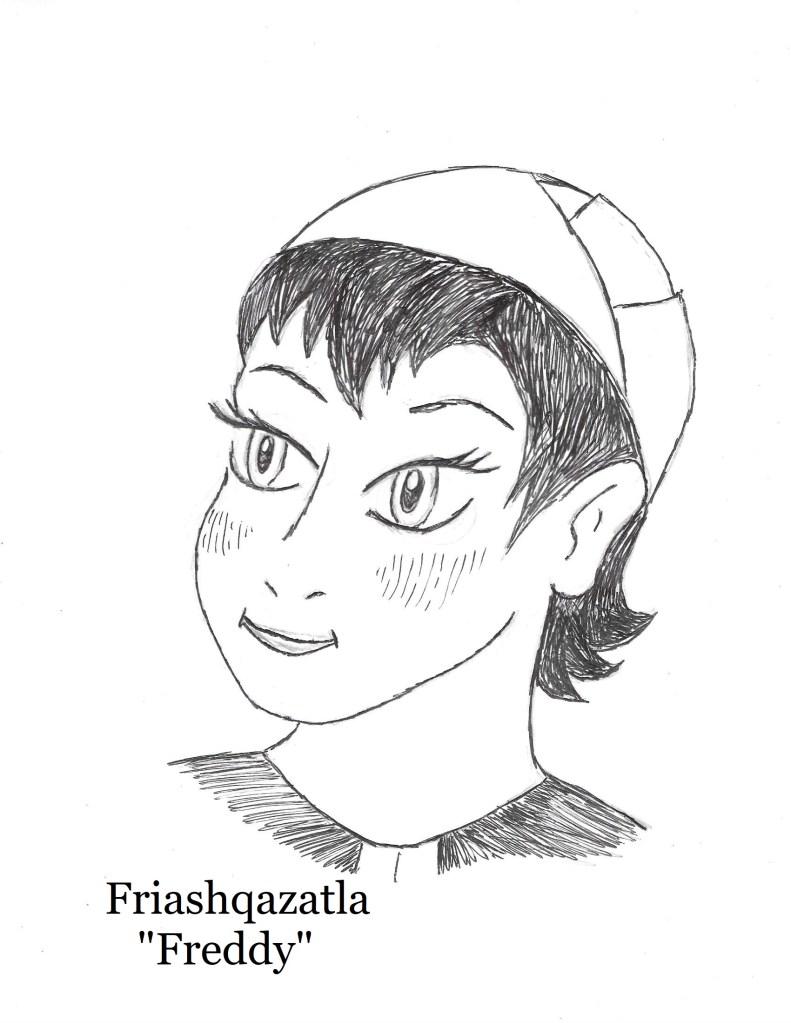

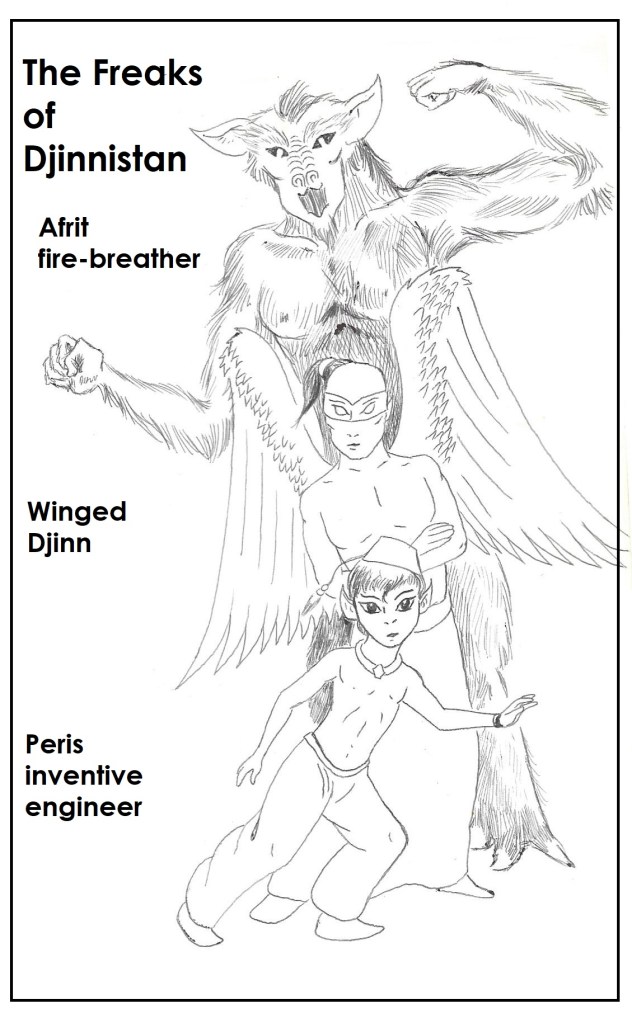

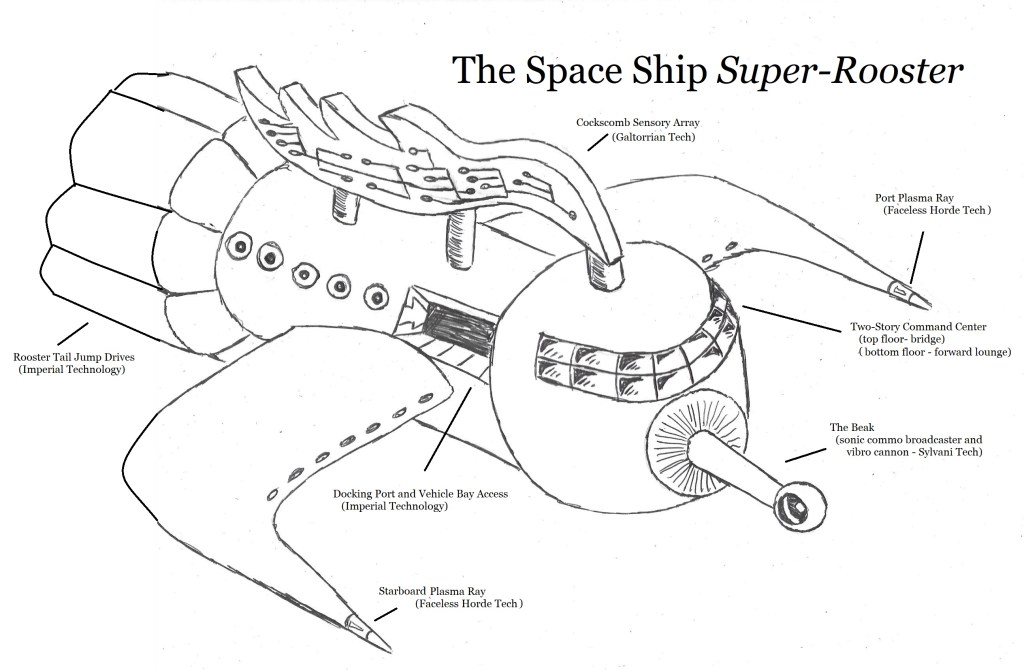

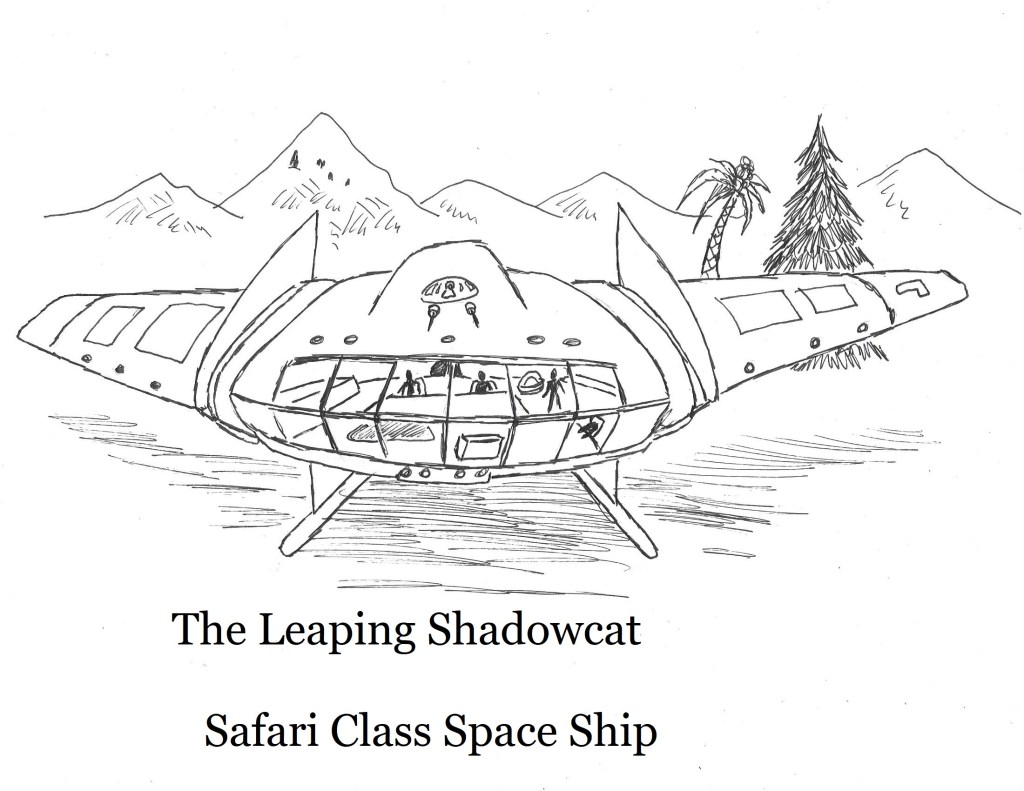

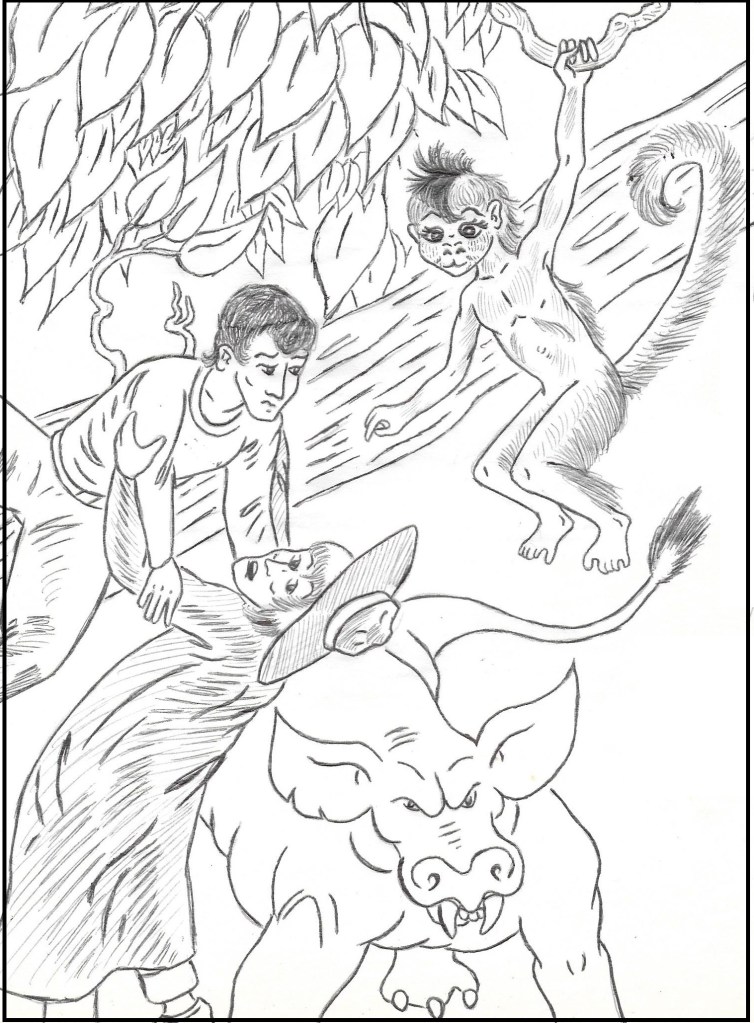

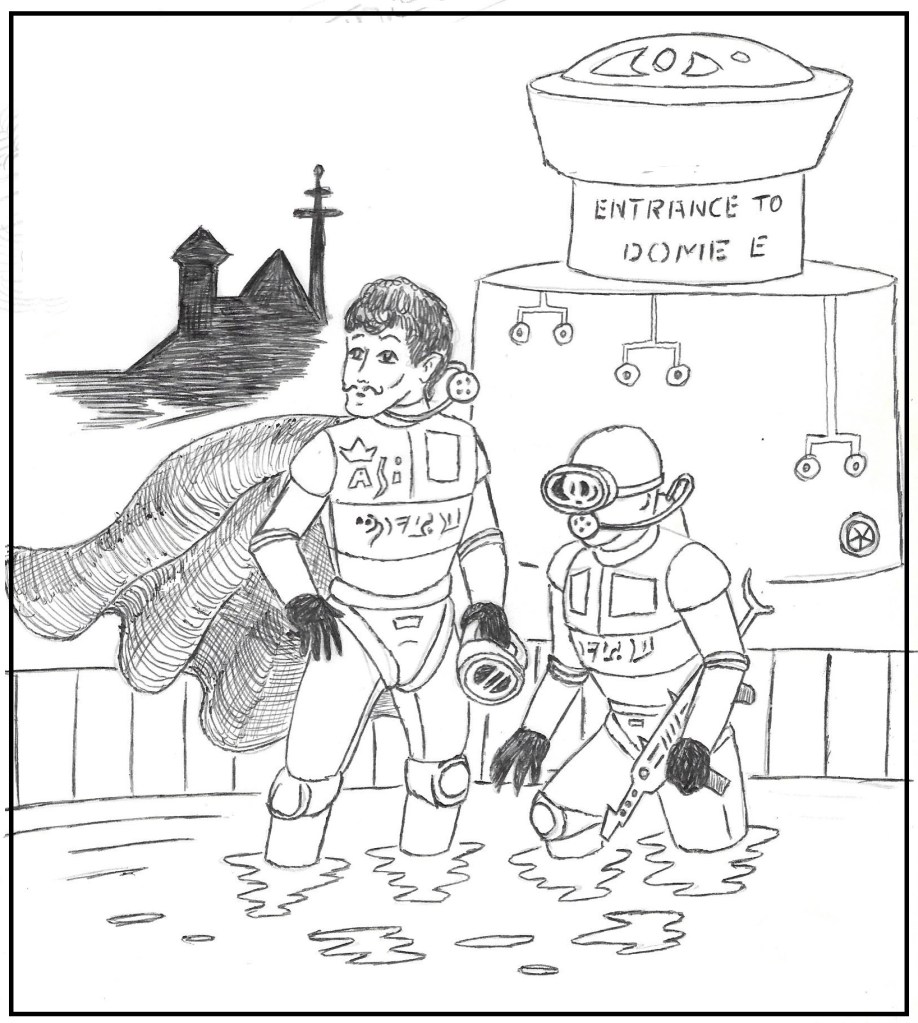

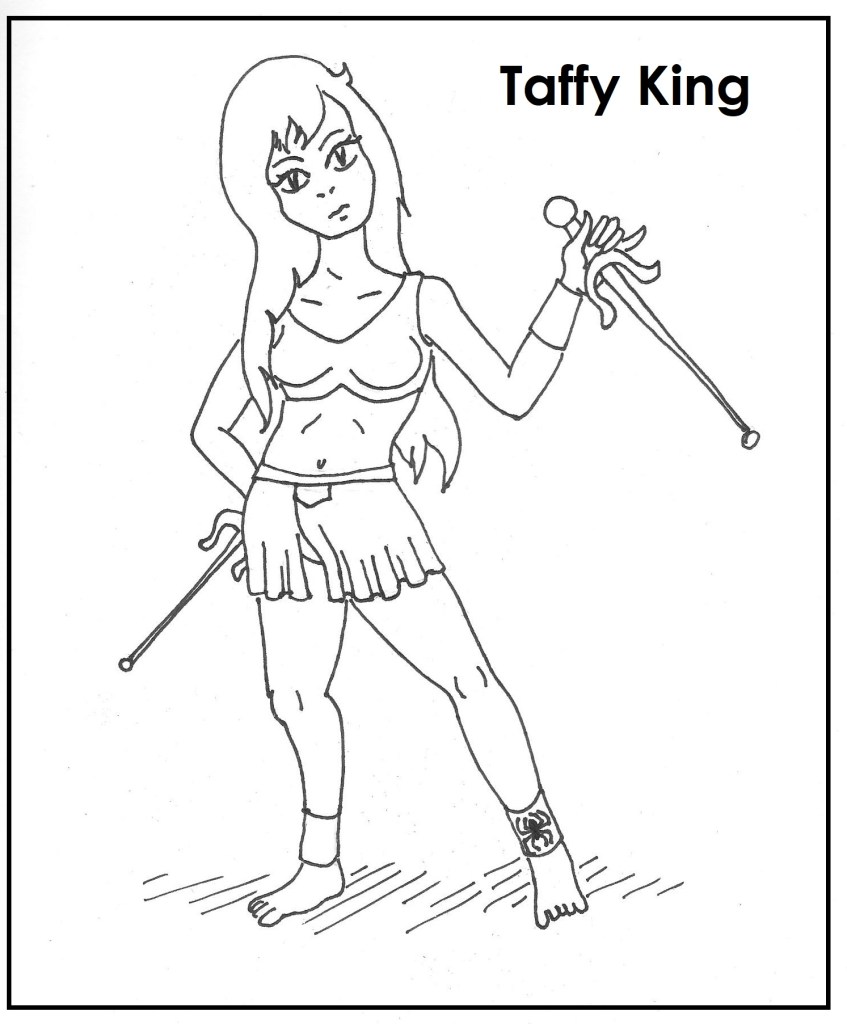

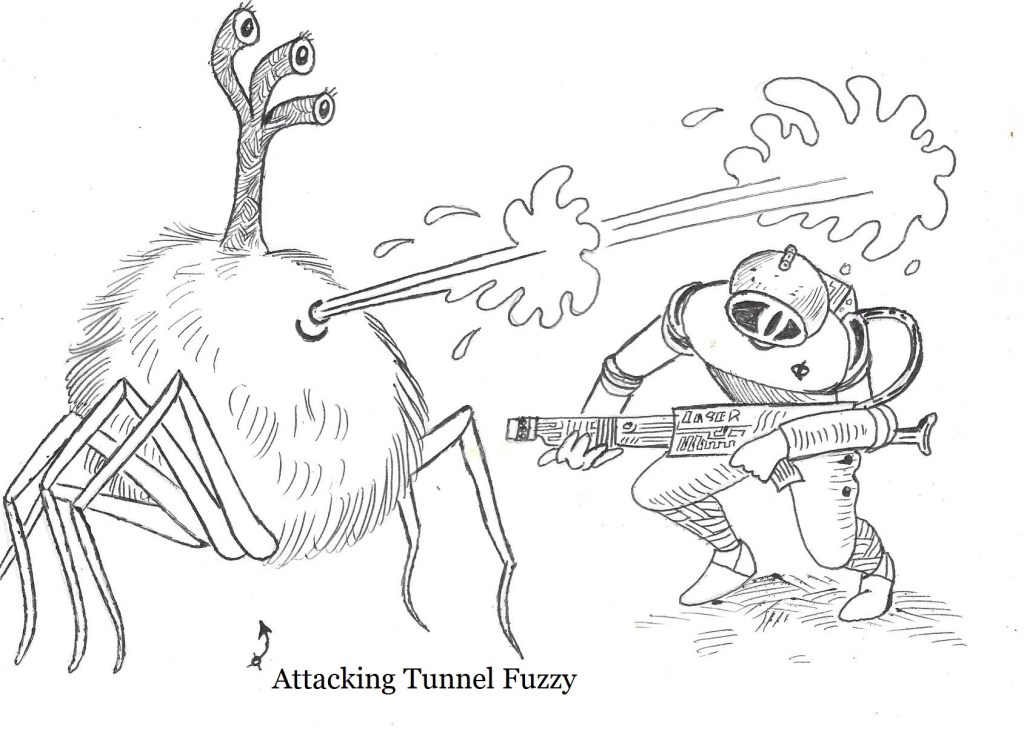

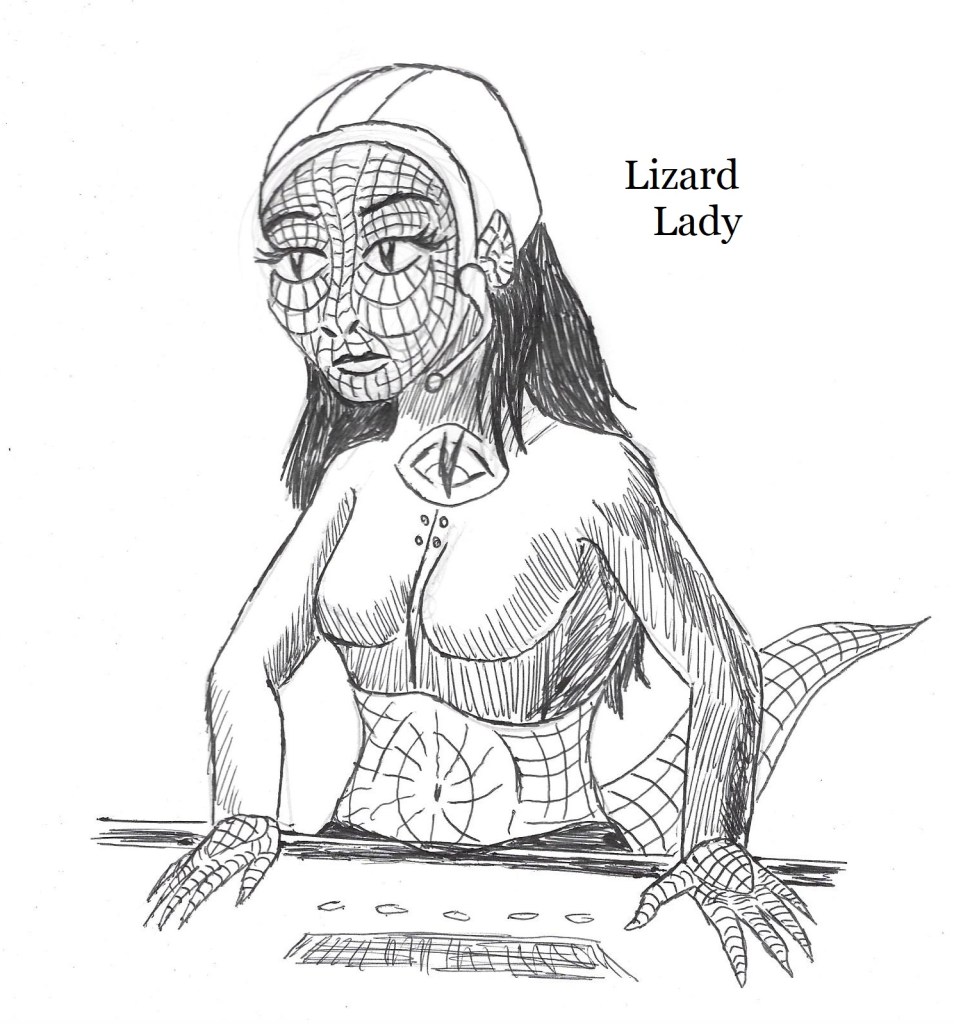

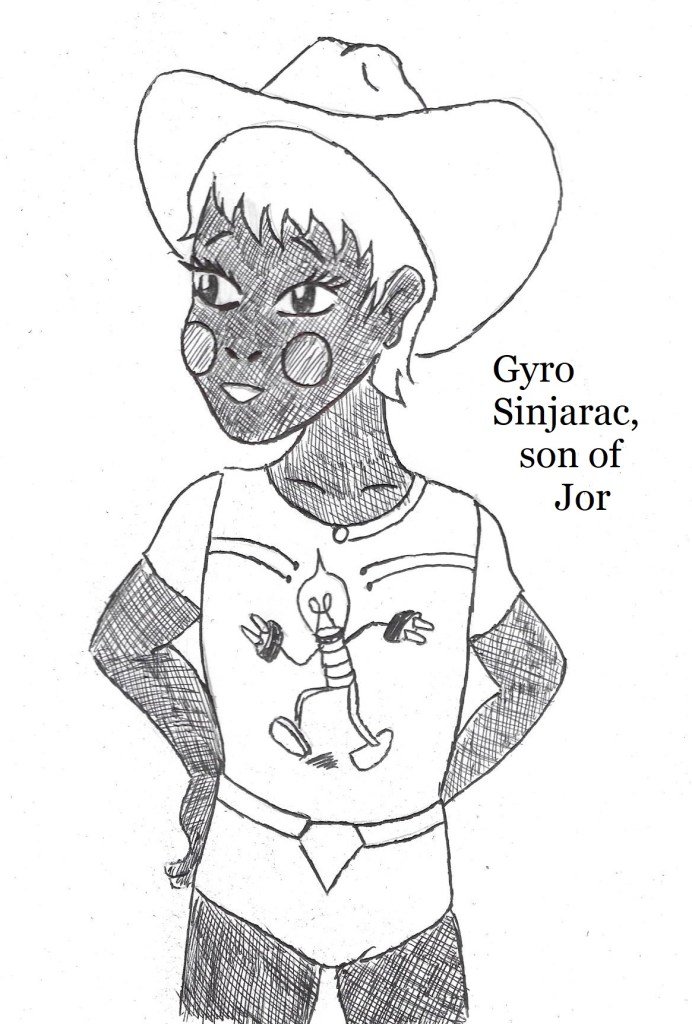

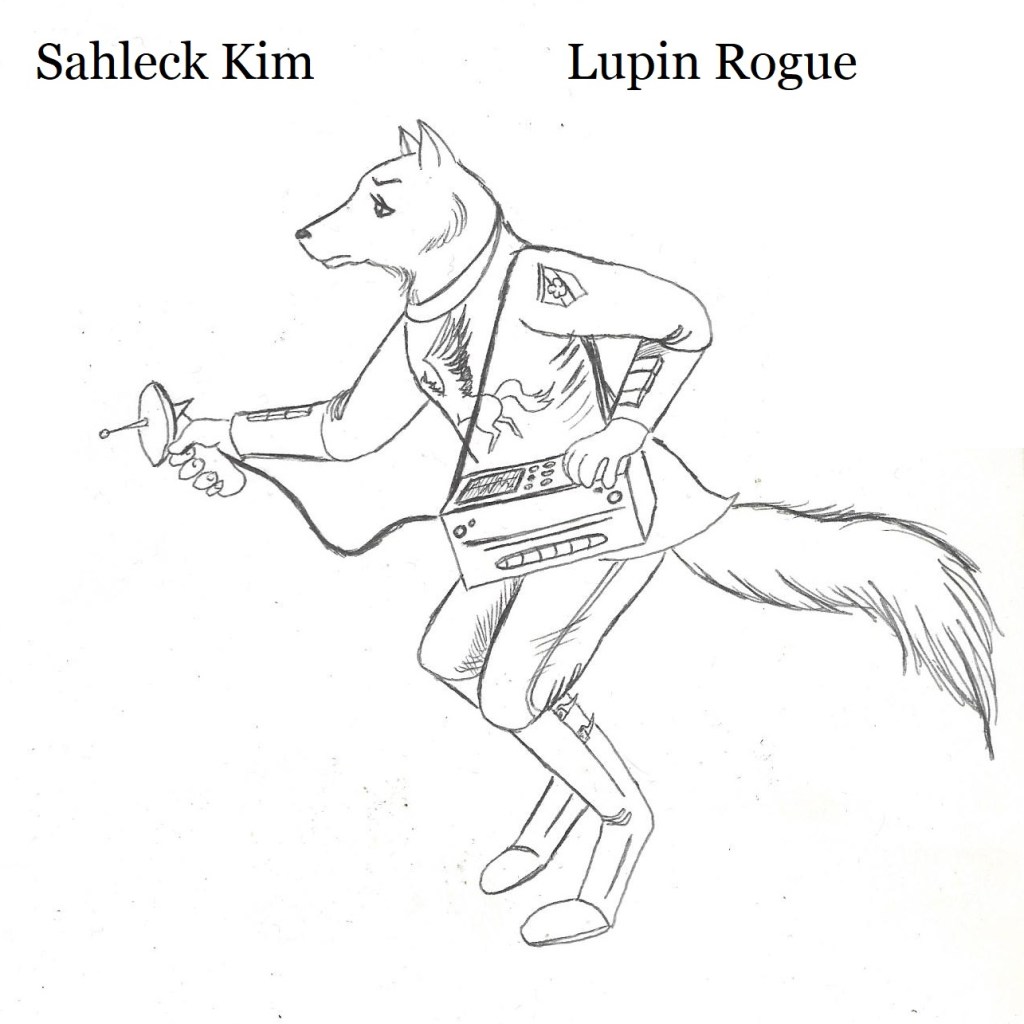

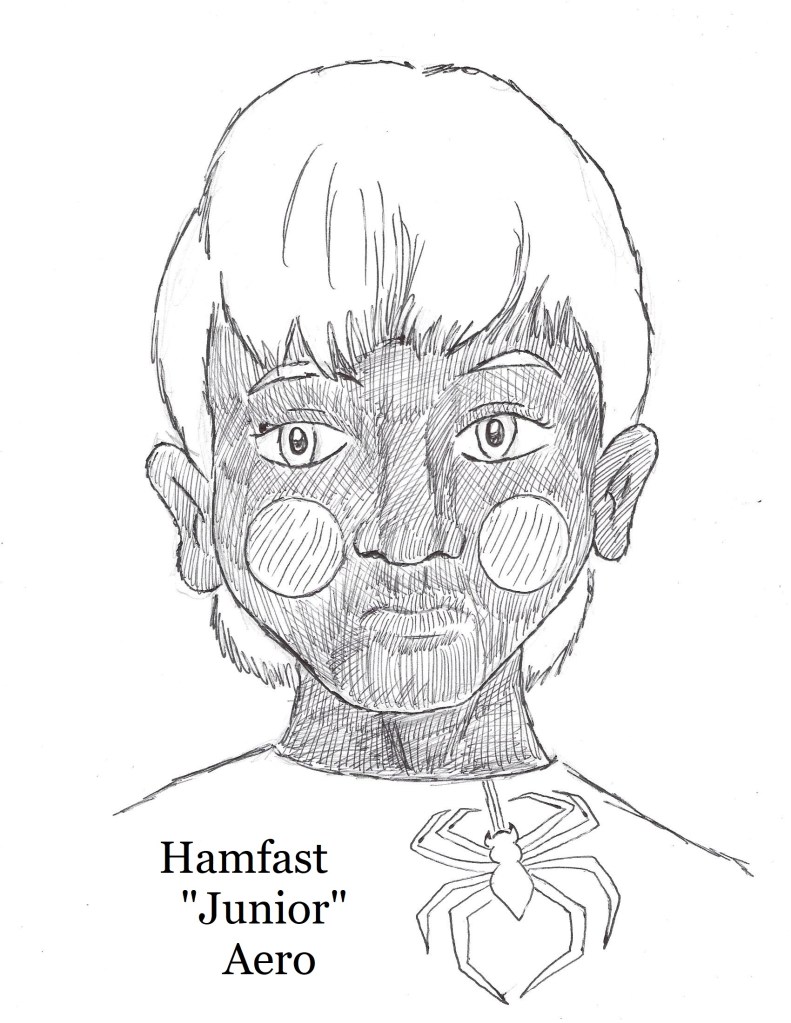

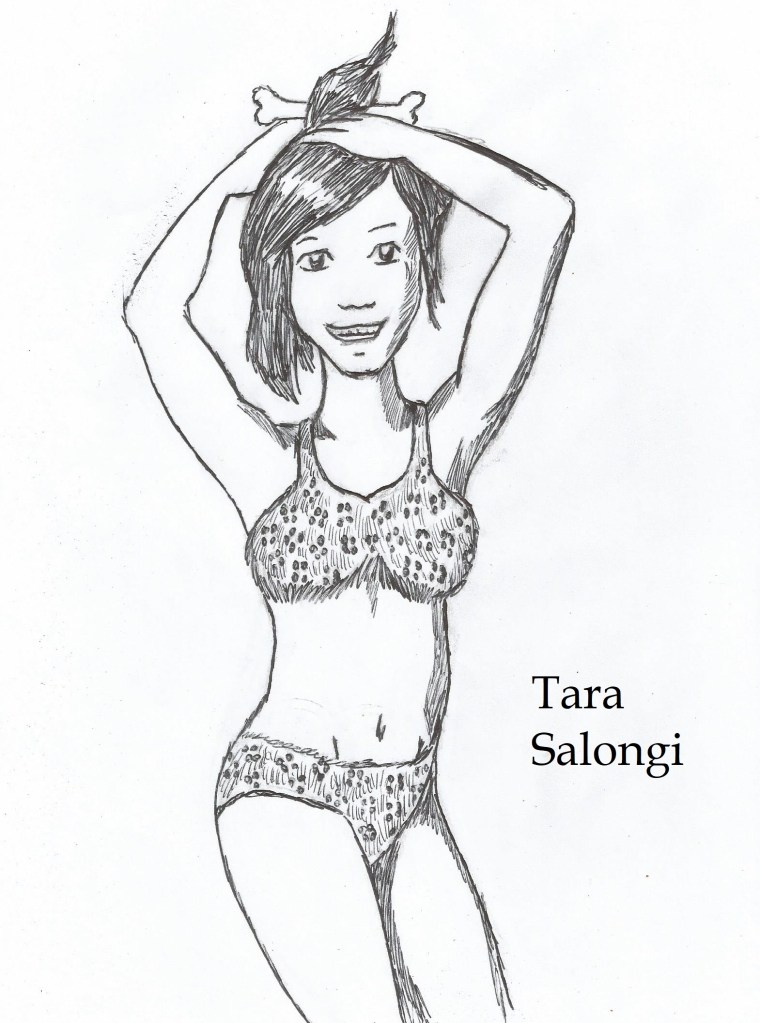

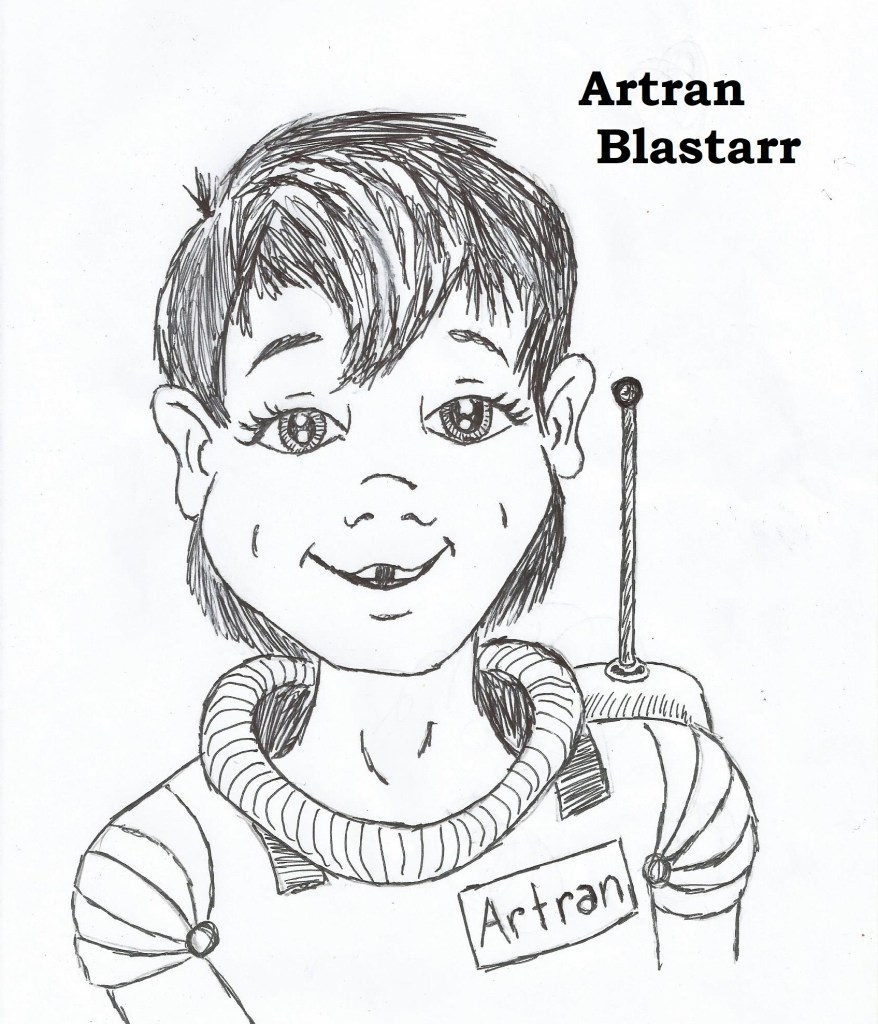

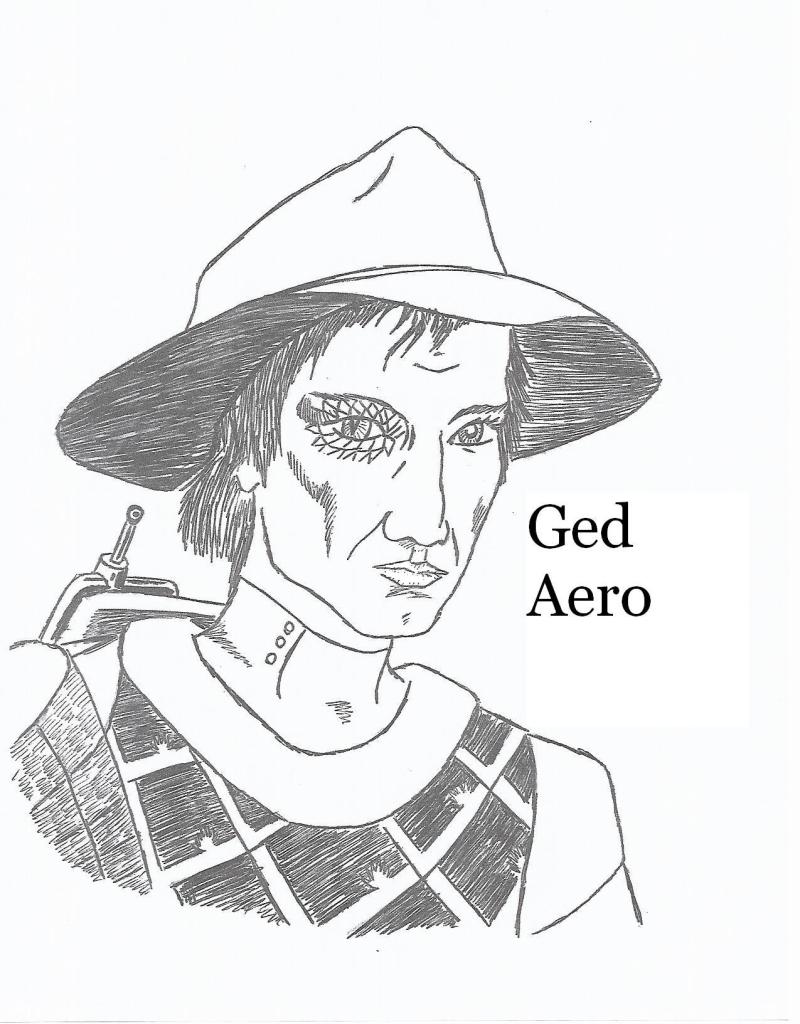

It’s just Mickey being Mickey. And a partially Paffooney gallery.

…To fill some space today.

And wonder about tomorrow.

And just be Mickey a little bit more.

Leave a comment

Filed under artwork, autobiography, cartoony Paffooney, commentary, goofy thoughts, humor, illness, Paffooney, self portrait, strange and wonderful ideas about life

Tagged as Mussorgsky, Pictures at an Exhibition